Closing in on a Killer: Scientists Unlock Clues to the Spanish Influenza Virus

This virtual exhibit makes widely available a 1997 temporary exhibit on the 1918 influenza pandemic and efforts by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) pathologist Dr. Jeffrey Taubenberger to recreate the genetic structure of the 1918 influenza virus.

This exhibit provides useful historical background on the pandemic and takes you step-by-step through the process that Dr. Taubenberger and his team of scientists used to fully reconstruct the 1918 influenza virus in 2005. At the time of the original exhibit, NMHM was an element of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) which held the largest and most comprehensive tissue repository in the world, including cases dating back to 1917 and more than 3 million medical cases overall.

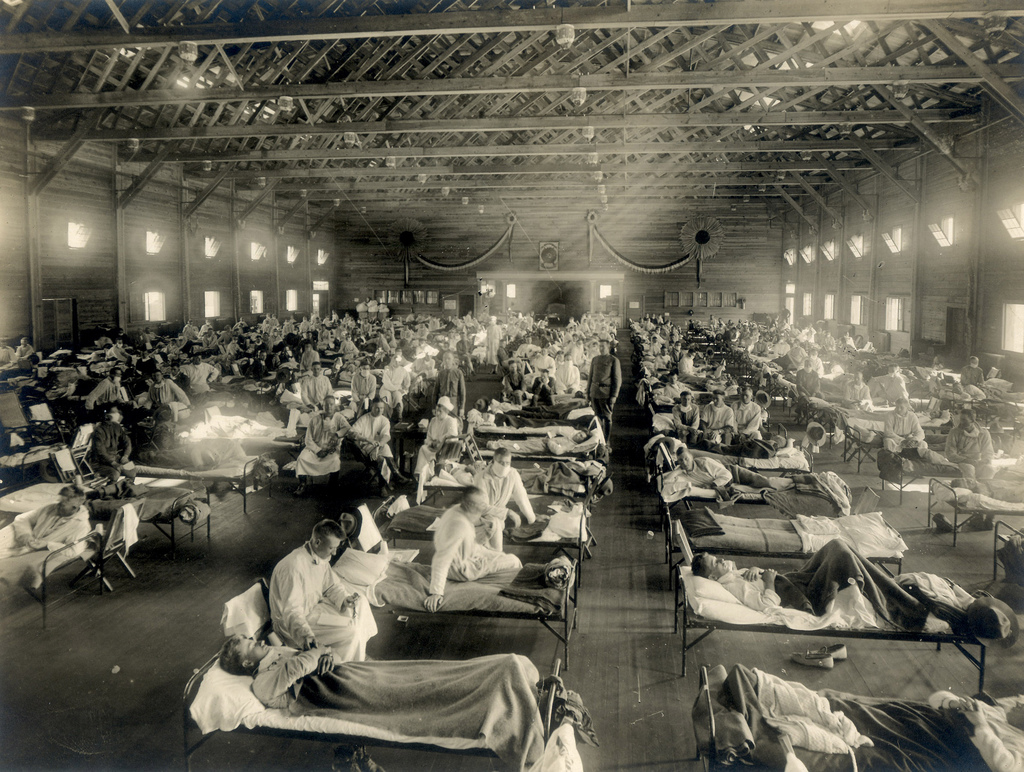

Emergency Hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas. (NCP1603)

Emergency Hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas. (NCP1603)

In 1918, an unusually deadly kind of influenza killed between 21 and 50 million people worldwide. What made this virus so deadly? Was it a completely new strain? Could it reemerge? For a long time, scientists have had more questions than answers about what has come to be known as the Spanish flu.

In 1996 there was a major breakthrough. Dr. Taubenberger and his team of scientists at AFIP were able to recreate fragments of genetic material of an influenza virus that caused the death of a soldier in 1918. They determined that it was a distinct strain of the influenza virus.

1918: Influenza Sweeps America

The influenza pandemic of 1918 swept the United States as the country was mobilizing for World War I. More than 25 percent of the population became ill and approximately 675,000 Americans died. Unlike most flu epidemics, which tend to be dangerous for children and the elderly, the 1918 influenza was lethal primarily to people from ages 20 to 40.

Camp Jackson Base Hospital medical staff, ca. 1918. (NCP 1310)

Camp Jackson Base Hospital medical staff, ca. 1918. (NCP 1310)

On Sept 19, 1918, Army Private Roscoe Vaughan reported to sick call at Camp Jackson, S.C. complaining of chills, fever, coughing and headache. His doctor noted that his face was flushed and his throat was congested. His heartbeat was regular, but he had trouble breathing. The physician concluded that Vaughan had influenza.

Four days later, Vaughan developed a secondary infection of pneumonia. By that evening, his pulse was feeble, and he appeared somewhat dazed. He lingered for three more days and died on the morning of September 26. He was one of over 43,000 U.S. servicemen who died of influenza in 1918.

An autopsy was performed on his body that afternoon. Samples of lung tissue were forwarded to the Army Medical Museum (later AFIP, and now the National Museum of Health and Medicine) for further study and preservation.

Autopsy instruments, manufactured by Kny-Scheerer and Co., ca. 1906. (M-001 00001)

Autopsy instruments, manufactured by Kny-Scheerer and Co., ca. 1906. (M-001 00001)

In 1918, there was little doctors could do to treat influenza except monitor body temperature and overall physical condition. Doctors would prescribe bed rest and a light, hot diet. Physicians dispensed aspirin to relieve pain and morphine to promote rest. There was no cure, and too often death followed illness.

A number of measures were adopted to prevent the spread of the influenza, including the mandatory wearing of cloth face masks. Other measures, such as administering antiseptic throat sprays, proved ineffective.

Preventive treatment against influenza, spraying throat, American Red Cross. Love Field, Texas, 11/6/18. (Reeve 33986)

Preventive treatment against influenza, spraying throat, American Red Cross. Love Field, Texas, 11/6/18. (Reeve 33986)

The lung shown here was infected during the 1918 influenza pandemic and exhibits bronchopneumonia. It was preserved as a wet tissue specimen and is currently on display at NMHM. (AFIP 0016635)

The lung shown here was infected during the 1918 influenza pandemic and exhibits bronchopneumonia. It was preserved as a wet tissue specimen and is currently on display at NMHM. (AFIP 0016635)

Continue reading to learn about the process Dr. Taubenberger used to reconstruct the 1918 influenza virus.