Ocularist helps patients keep an eye on tomorrow

By Paul Bello, National Museum of Health and Medicine

SILVER SPRING, Md. - A passion for art has led Louis Gilbert down a unique path. One that's personally rewarding and deeply meaningful to the people he meets.

Gilbert, an anaplastologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), crafts handmade prosthetic eyes, in addition to ears, noses, dental implants and other facial features that may be missing due to an individual's birth defect, disease, combat or trauma. Also referred to as an ocularist, he offered a presentation entitled "Making Them Whole: Ocular Prosthetics," during the National Museum of Health and Medicine's (NMHM) monthly Medical Museum Science Café, held Sept. 22, 2015.

His predecessor, Vince Przybyla, worked at the previous Walter Reed for 38 years. Many of his tools and prosthetics are part of NMHM's historical collections and were on display to coincide with Gilbert's presentation.

Gilbert, who previously served 20 years in the U.S. Navy, is a dental technician for the Department of Defense. He received training in maxillofacial prosthetics while attending the Navy's Postgraduate Dental School in Bethesda, Maryland. Gilbert provided a historical overview of his profession, which dates back to as early as fifth century B.C. when Egyptian priests would make eyes from painted clay. Ocular prostheses were first seen in the U.S. in the mid-1800s and today are predominantly made of hard, plastic acrylic, according to Gilbert. They are also removable.

"When making prosthetic eyes, the goal is to simply make it as life-like as possible and to have it move as best as possible, " Gilbert told the audience. "I get started by taking an impression with an alginate material. I then squirt the material inside the surface of the eye socket. This is done with the same type of material used to take a mold of the teeth."

Once he has the impression, Gilbert makes a mold with hot wax. After gently smoothing it out so it fits to his patient, he places it inside the eye socket and uses a marker to mark the spot where the pupil will be. With more than 30 years of artistic ability at his fingertips, his goal now is to make a perfectly straight eye.

"The last thing you want is to make a prosthetic eye for a person and have it look cross-eyed," Gilbert said. "Every prosthetic eye is also painted based on what the patient looks like, as well as their existing eye. I also make a point of measuring the painted iris and pupil so they look aesthetically correct."

Gilbert uses regular oil paints and monomer as a painting medium. His five colors of choice are blue, red, yellow, white and green. And with those five colors, he can get any color he wants. Interestingly, he never uses blue for people with blue eyes. The eyes are actually gray, according to Gilbert, but just look blue.

Once the eye is completely painted, he embeds the painted iris into a wax mold. He then makes a stone mold using red thread to simulate the capillaries inside the eye. A clear coat of acrylic then seals everything before being delivered to the patient. A hydroxy appetite or quarrel implant is also used to attach muscles behind the tissues so an individual has movement, he said.

Typically the process for making a single prosthetic eye takes about eight hours from start to finish, Gilbert said. Three hours of the patient sitting in a chair, with the other five hours dedicated to sculpting, polishing and finishing the eye.

Specialty eyes are also part of Gilbert's line of work. To date, he's created prosthetic eyes for wounded servicemen paying homage to Captain America and different sports teams.

"It's important to have patience. It takes time to get things just right," Gilbert said at the conclusion of his presentation. "It's a rewarding job because I'm able to change their lives. The feeling I get out of making someone feel whole is incredible. I really can't describe it."

NMHM's Medical Museum Science Cafés are a regular series of informal talks that connect the mission of the Department of Defense museum with the public. NMHM was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 and moved to its new location in Silver Spring, Md. in 2012. For more information, please call 301-319-3303 or visit www.medicalmuseum.mil.

|

Caption:

Prosthetic eyes, made by Louis Gilbert, anaplastologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC),

were on display during the National Museum of Health and Medicine's monthly Medical Museum Science Café, held Sept.

22, 2015. Gilbert was this month's guest speaker. (National Museum of Health and Medicine photo by Paul Bello / Released) |

|

Caption:

Louis Gilbert, anaplastologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), discusses the history

and process involved with prosthetic eye making during the National Museum of Health and Medicine's monthly Medical

Museum Science Café, held Sept. 22, 2015. (National Museum of Health and Medicine photo by Paul Bello / Released) |

|

Caption:

Louis Gilbert, anaplastologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), shows what a painted iris

looks like during the National Museum of Health and Medicine's monthly Medical Museum Science Café, held Sept. 22, 2015. (National Museum of Health and Medicine photo by Paul Bello / Released) |

|

Caption:

Visitors look over an array of prosthetic eyes and other maxillofacial prosthetics during the National Museum of Health

and Medicine's monthly Medical Museum Science Café, held Sept. 22, 2015. (National Museum of Health and Medicine photo by Paul Bello / Released) |

|

Caption:

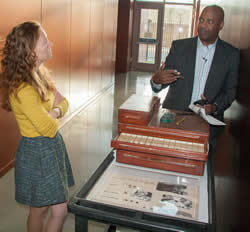

(Right) Louis Gilbert, anaplastologist at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (WRNMMC), speaks with Caroline

Bradford, museum specialist at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM), prior to Gilbert's presentation on

prosthetic eye making, Sept. 22, 2015. Bradford displayed a cabinet and workstation used by Gilbert's predecessor, Vincent

Przybyla, ocularist at Walter Reed for 38 years. Pryzbyla's collection of tools and prosthetics is part of the NMHM Historical

Collection. (National Museum of Health and Medicine photo by Paul Bello / Released) |