Brain Awareness Week Highlights Military Medicine's Contributions to Brain Sciences

By Lauren Bigge

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

Advances in helmet design and body armor, developments in diagnosis and treatment of head injuries, and the positive role of training service animals was all part of Brain Awareness Week (BAW) at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM), a Department of Defense (DoD) museum in Silver Spring, Md. March is recognized as Traumatic Brain Injury Awareness Month by the DoD each year.

BAW, now in its 18th year at NMHM, is an annual event bringing together middle-school students with the museum's education partners, including subject matter experts from government agencies and military medical research agencies. BAW was founded by the Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives, an organization dedicated to advancing brain research.

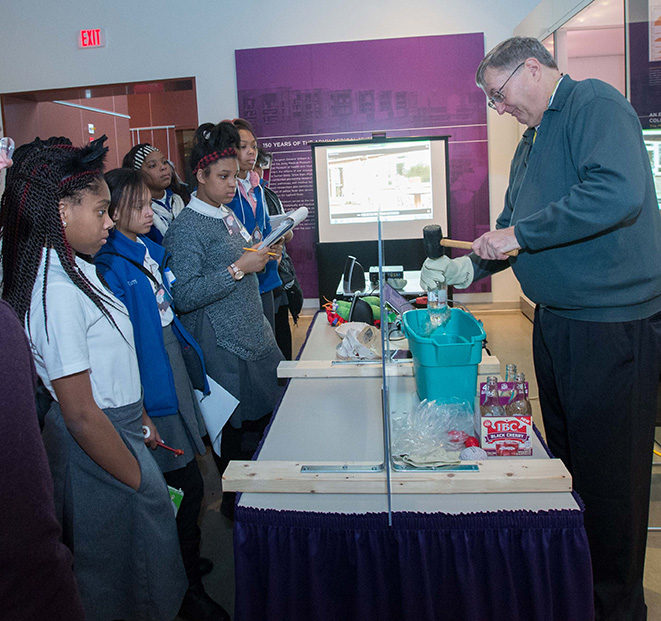

At one station, the students were awestruck to watch a glass bottle's bottom break off in one clean piece, and the water spill into a bucket, when Dr. Tim Bentley, Office of Naval Research, Force Health Protection, tapped the open bottle top with a mallet. Bentley demonstrated how mantis shrimp make cavitation bubbles, which form when water is "torn" by great strain, and related how those cavitation bubbles are similar to the pressure waves that emanate from an explosion, such as that which a service member might experience while deployed or in training. The U.S. Navy is concerned about service members suffering brain injuries from explosive blasts. "We're interested in how those forces injure our people, and what we can do to protect them," he said. "To do that, we really need to know how they're injured." Studying mantis shrimp cavitation bubbles might help lead to innovation in helmet design, for instance.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) prevention and treatment was the focus at other stations, too.

Students tried on flak jackets at the Naval Medical Research Center station and heard about how low or moderate level blasts affect the brain and how lesser trauma, such as a blow to the head while playing sports, can hurt the hippocampus. Students visiting the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center station learned about the major causes of TBI and participated in a "Brain Drop," which involved dropping eggs that had been padded to simulate head protection and then watching the shells crack (or not) as they hit the floor. The lesson: wear appropriate head protection.

The "Barrier Game" by the Speech Pathology Clinic at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center's National Intrepid Center of Excellence helped students understand thinking and communication problems after brain injury. Each team was challenged to use colored shapes to create a specific shape, on either side of the barrier, with the opposing team providing verbal directions.

"Throughout the activity, they'll learn they may have to change their communication style to get the other team to improve their performance," said Shannon Auxier, speech pathologist. "This will help demonstrate how in speech therapy in the Brain Fitness Center, we're using different therapy techniques to help those who've had a head injury learn how to communicate and use their thinking skills."

Another theme of BAW: the brain – senses connection.

At the "Map Your Own Homunculus" station, Emily Kuehn, Ph.D., from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research had students make cartoons showing how tactile perception is represented in the brain, while they learned how sensory information gets transferred from the skin to the brain. "Homunculus means ‘little man' – the idea is that this [cartoon] represents that there's a little man in your brain, and he's in proportion to what you sense in your schematic sensory cortex," she said. "My goal is to get them excited about what the brain can do."

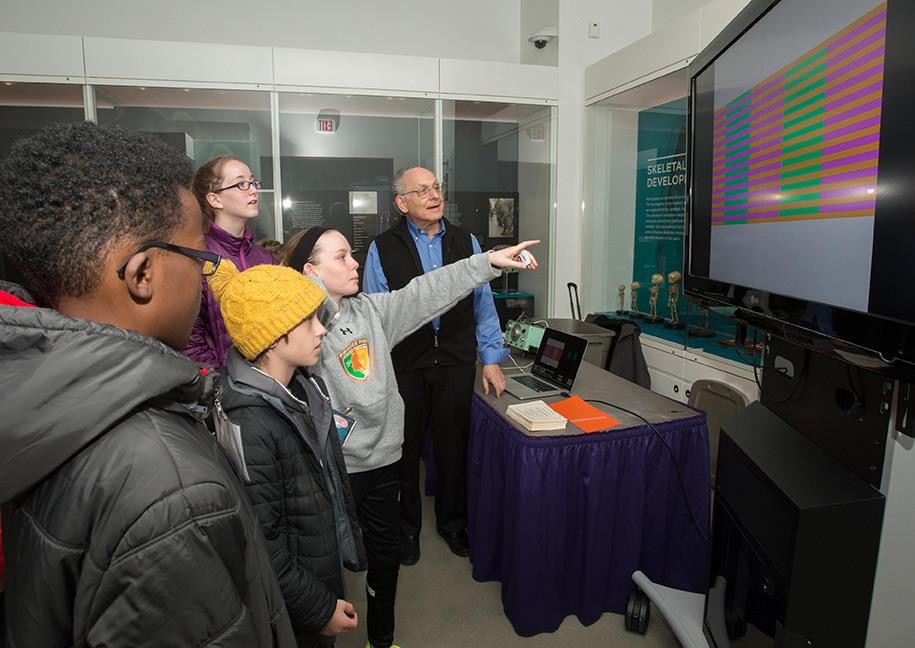

Students learned you can't always believe your own eyes, after experiencing brain teasers at the "Seeing is Believing (Or is it?)" station. They saw optical illusions involving duplicate sketches and tricky backgrounds, and tried a Stroop Effect test. Barry R. Komisaruk, Ph.D., Distinguished Professor, Department of Psychology, Board of Governors Distinguished Service Professor, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, explained that it's all about context; the brain has to put information together.

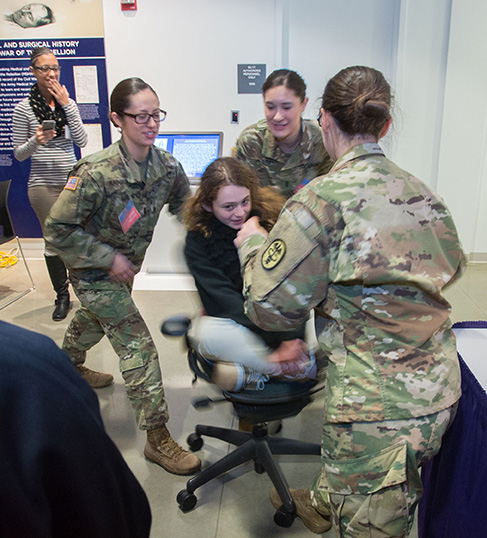

Ears are crucial to hearing and balance, so Walter Reed National Military Medical Center's Audiology Clinic representatives set up three ear-brain connection demonstrations: ear anatomy and how the brain processes sound; hearing protection and noise hazards; and how semi-circular ear canals (the vestibular system) affect balance.

LTC Amy Blank, director of Walter Reed's audiology clinic, pointed out the noise hazard demonstration – a mechanical ear with an earphone in it, connected to a music source. "We're showing the children how turning up the volume affects the decibel level," she said. "About two thirds volume above [what they heard] is noise hazardous." They also saw that an earplug properly sealed in a funnel can protect hearing when water enters. The final, fun learning experience was how vision, the somatosensory system (feeling solid ground beneath the feet), and semi-circular ear canals work together. The students stood on a foam block with open eyes, then closed their eyes, were spun around in a chair, and then stood on the foam again with their eyes closed. "You really need all three of those working in concert to have good balance," Blank added.

Students were fascinated by the human brain's ability to control a prosthetic, thanks to a presenter from the Paralyzed Veterans of America. They shook the robotic hand of a Vietnam War veteran with an amputated left arm who participates in a research study for this technologically innovative prosthetic arm, provided by DEKA Research and Development Corp. Fred Downs, Jr. has battery-powered control signals attached to his shoes that guide the DEKA Arm up and down or sideways so he can grasp a heavy bag, shake hands, grip objects of various sizes, and even cook for himself (with a glove over the hand). He showed the students that the left and right units are designed to signal different movements, so he must constantly think in order to move the prosthetic the way he wants it to go. "I have to pay attention to everything I am doing," Downs said, as he demonstrated the process it takes to shake a hand.

The students also learned about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) by talking to a yoga therapist and meeting some service dogs in training.

Lynn Valdes, from Walter Reed's Mind-Body Program, spoke about using the tools of yoga to help service members and veterans manage PTSD symptoms. "Breathing is one way to regulate your autonomic nervous system," she said. "We're going to move through a few postures with breaths," adding that breath-centric movement may help calm nerves before a test or a presentation.

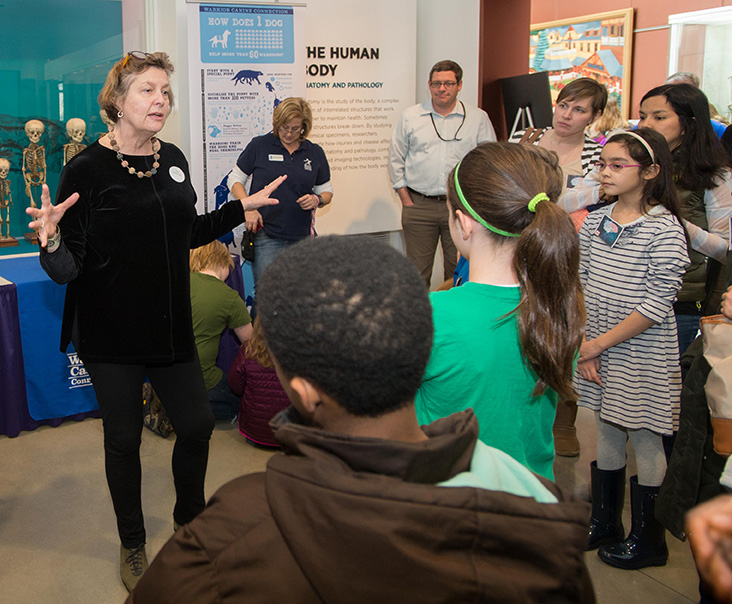

Service members and veterans who have experienced PTSD are now training dogs for wounded warriors, Meg Olmert, Warrior Canine Connection Senior Research Advisor, explained to students at another station, as she encouraged them to pet several dogs participating in the presentation. Studies have shown that training service animals can reduce PTSD symptoms. "The kind of high quality social engagement it takes to train a young dog is very much like parenting, and supported by the same brain systems because dogs and humans have very similar social brains," Olmert said. "Dogs are able to elicit our brain chemistries that support anti-stress, and social behavior, which are the underpinnings of many of the problems with PTSD." After two years of training, the dogs are placed with wounded warriors.

BAW at NMHM supports the Department of Defense's science, technology, engineering and math –STEM – development priorities. The BAW program is closely aligned with performance expectations for middle school students as described in the Next Generation Science Standards promoted by the National Academy of Sciences.

Click any photo to view larger version