Journalist Shares Wartime Race to Find Malaria Cure

By Lauren Bigge

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

Malaria was devastating America's armed forces in the South Pacific during World War II, so the U.S. War Department and the White House recruited more than 400 scientists to find a cure. Journalist Karen M. Masterson's research into their work resulted in her book, The Malaria Project: The U.S. Government's Secret Mission to Find a Miracle Cure, the details of which she shared with the Medical Museum Science Café audience at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Md. on May 23.

She told attendees that parasites from mosquitoes assault red blood cells, feeding on the hemoglobin. "Every other day, a fever will spike – up to 107 degrees," she said. "Malaria is a rough disease."

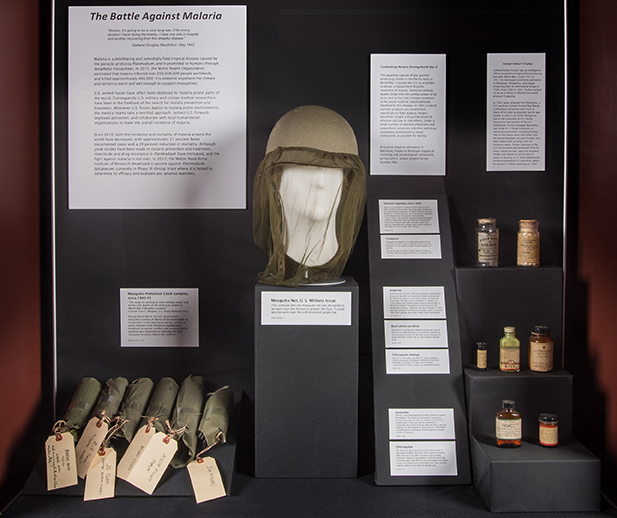

"The Battle Against Malaria" exhibit, which was on display at NMHM through June 2017, included models that showed the incubation cycle of four strains of malaria parasites in human red blood cells. Mosquito netting and medication bottle samples documented efforts used to combat malaria at that time.

Masterson described how American biologist and malaria expert Lowell Coggeshall learned about malaria research conducted in Germany during World War II. He proposed a massive drug research project to the War Department.

"Malaria was everywhere," Masterson said. "[Coggeshall] became the most innovative thinker on malaria." Coggeshall told the War Department that treatment wasn't enough; prevention was also needed. The War Department showed little interest at first, because U.S. camps where troops trained were sanitized against mosquitoes. They also knew they had stores of quinine medication to fight infections once the men shipped out. However, quinine supplies dwindled. Malaria infections continued. In the Pacific, Marines fell ill by the tens of thousands, despite sanitation efforts. Troops were forced to take the drug atabrine as a prophylactic, but it made them sick and many refused the medication.

"The War Department turned on its propaganda machine," Masterson said, referencing advertisements illustrated by Theodor Geisel, a.k.a. Dr. Seuss., in the Army's animation department (reproductions of several advertisements were part of the temporary exhibition at NMHM). The advertisements were intended to encourage troops to take preventive measures against malaria infection, and to stay on atabrine.

Leading scientists came together in a new, secret "Malaria Project." The U.S. Public Health Service founded the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas (predecessor of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Their work was urgent; the total number of infected service members in all theaters would reach half a million by the end of the war.

In September 1943, the "Malaria Project" group discussed a drug called sontochin from a Germany laboratory. Testing its chemical structure revealed that the Rockefeller Foundation's Coggeshall and John Maier had already tested it in 1941. They got their samples from the Winthrop Chemical Company, which held the sontochin patents. Winthrop chemists had put it aside, ignoring the positive Rockefeller conclusion. In 1942, human studies showed sontochin to be less toxic than atabrine and more active against malaria.

"This drug came back to the United States, and it was like an 'ah-ha' moment," Masterson said. "The scientists could unify around this compound. They had samples of it."

By 1944, the "Malaria Project" had investigators working on the synthesis of drugs, animal testing, and human studies. Alf Alving, University of Chicago medical professor, became a lead investigator and went to Stateville Penitentiary to conduct clinical trials.

"He was smarter than the others in that he didn't rely on civilians; he trained prisoners to do the work," Masterson said, recounting that Alving taught inmates microscopy and drug administration. They gave malaria and experimental drugs to other inmates, in an informed consent environment. Female anopheline mosquitoes bit inmates. Alving then tried the sontochin analogue SN-7618 on his subjects, Masterson said, experimenting with the dosage; it worked to treat malaria, with mild to nonexistent side effects.

The U.S. government started developing SN-7618 for license-free production. After World War II, SN-7618 – now named chloroquine – was used globally, along with DDT, in the World Health Organization's Global Malaria Eradication Programme. Mosquitoes developed DDT resistance, however, so WHO began using chloroquine extensively for treatment beginning in the 1950s.

"Every basic molecule for every drug that we use against malaria that was made in America came from this project," Masterson concluded.

"Ms. Masterson opened our eyes to the methods researchers used during World War II to develop preventive measures and treatments for malaria, illustrated by the temporary exhibit at the museum," said Andrea Schierkolk, NMHM public programs manager. "The museum has documented military medical research that has led to the prevention and treatment of malaria infection in the armed forces for many years."

NMHM's Medical Museum Science Cafes are a regular series of informal talks that connect the mission of the Department of Defense museum with the public. NMHM was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 and moved to its current location in Silver Spring, Maryland, in 2012. NMHM is an element of the Defense Health Agency. For information on upcoming events, please call 301-319-3303 or visit www.medicalmuseum.mil.

Click any photo to view larger version