Military Medical Museum Acquires Prototype "Bioprinter" From Wake Forest Institute For Regenerative Medicine

By Lauren Bigge

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

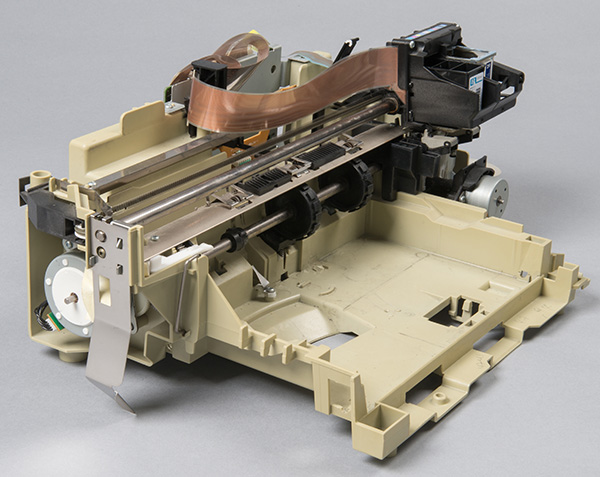

The National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) recently acquired a "bioprinter" that researchers at the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine (WFIRM) developed to demonstrate that it was possible to "bioprint" 3-D organs.

NMHM, a Department of Defense museum and a division of the Defense Health Agency Research and Development Directorate, acquired the printer with support from the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine (AFIRM). AFIRM helped fund the initial development of the Wake Forest bioprinter as part of the institute's initiatives to develop rapidly-evolving technologies to treat the most severe injuries American service members are suffering on today's battlefields, such as debilitating burns.

Since 2003, the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research Burn Center has treated more than 1000 military burn casualties injured in support of overseas operations. Bioprinting is emerging as an innovative tool to care for members of the American military who have suffered severe burns.

WFIRM used the bioprinter in projects that included: printing skin equivalents, bone structures using amnion-derived cells, a miniature multi-chambered structure with heart cells; and multiple cell types in one construct. WFIRM's scientists multiplied cells in a petri dish and mixed with those a biocompatible substance that was put into a 3-D printer "bioink" cartridge. The printer was programmed to arrange different cell types and other materials, which were then distributed into a precise three-dimensional shape.

"This was the very first printer to prove the concept that one could 'print' implantable tissues," said Alan Hawk, manager of the museum's Historical Collections. "That's a rare thing to see in history. That's why we wanted it for the collection; we wanted to make sure it was preserved alongside other historic innovations in the field of regenerative medicine."

Hawk noted that AFIRM was instrumental in facilitating the transfer of the bioprinter to the museum.

The Department of Defense established the AFIRM network in 2008, out of a need for human cells, tissue components, and organs for service members with debilitating injuries. Today, AFIRM research focus areas encompass skin, extremity, craniofacial, genitourinary, and vascularized composite tissue transplantation. The AFIRM consortium is led by Wake Forest University and AFIRM is managed and funded primarily through the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command.

The idea for the acquisition first began when Kristy Pottol, former project manager in the Tissue Injury and Regenerative Medicine Office of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, visited Dr. Anthony Atala's lab as part of a routine site visit, saw the printer there and discussed where the technology is headed. Because Atala conducts an annual AFIRM investigators meeting in the D.C. area, Pottol suggested and helped coordinate, an AFIRM investigator 'field trip' to the museum. "A number of regenerative medicine researchers came to the museum for the field trip and the enthusiasm and magic of the NMHM staff opened the door for the acquisition of a few artifacts, the printer being one," Pottol said. "This is a great story for both organizations in the commitment to the medical care of the wounded warfighter."

According to WFIRM, results of bioprinting research indicate that printed structures have the right size, strength and function for use in humans. A series of experiments proved the feasibility of printing living tissue structures that could be implanted experimentally and could replace injured or diseased tissue in patients in the future.

"It's still very experimental; [scientists] have proven they can print hollow organs," Hawk said. "They're starting to look at printing more complex organs, and the skin grafting is probably one of the best applications of the technology so far."

NMHM has artifacts documenting the history of precursors to regenerative medicine such as models of facial reconstruction from the Civil War through the Vietnam War; tattoo machines (needles) for facial and eye pigmentation; and dermatomes, which can remove skin from one part of the body and re-locate it where needed as is sometimes the case for burns. However, the addition of the proof-of-concept bioprinter was a distinct triumph for the Historical Collections department.

"Dr. Atala's team has been working on bioprinting for many years," Karen Richardson, WFIRM's communications manager, said. "The original printer played a large role in research that led to the Armed Forces Institute of Regenerative Medicine, so it was a natural fit to donate it to the museum, with its vast collection of specimens and artifacts for research in military medicine and surgery."

"What's interesting and exciting about this is it's the beginning of an idea," Hawk said. "It's a story that is still emerging."