Bone-anchored Prosthetics are Life-changing Innovations for Wounded Service Members

By Lauren Bigge

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

Technological innovations in prosthetics can improve the lives of service members with limb amputations, said Navy Cmdr. (Dr.) Jonathan Forsberg during a Medical Museum Science Café at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, a Department of Defense (DoD) museum, on June 26.

Forsberg and Army Lt. Col. (Dr.) Kyle Potter lead one of the first osseointegration programs in amputation surgery at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Osseointegration is a procedure to implant a device directly into a bone that exits the skin and attaches to a unique functional prosthesis. The external prosthesis attaches directly to the skeleton; no soft tissue required. Osseointegration allows for precise movement of prostheses and the ability to feel where the residual limb moves in space. This concept is intended for patients who experience difficulty with socket-based prosthetics.

"Your immune system was designed for the closed fracture, the saber tooth tiger bite, the insect bite," Forsberg said. "It was not designed for a blast, which is really a systemic injury. What we see, is massive amounts of inflammation that drives a primitive—but overwhelming—healing response that can lead to complications such as heterotopic ossification, or bone that forms in the soft tissues." Other complications such as wound infections and extensive scarring can also make it exceedingly difficult for patients with amputations to bear weight and lead normal lives.

To overcome such problems, Forsberg and Potter worked with a committee comprised of armed forces members and osseointegration and bone physiology experts from around the world, then traveled to gain hands-on experience with every osseointegrated system that was commercially available both domestically and internationally. The result: an implant uniquely suited for patients with blast injuries.

Forsberg and Potter began clinical trials at Walter Reed in February 2016. A patient received the first compress-based, osseointegrated prosthesis implant in May 2016. Forsberg noted that the Transhumeral Amputee Osseointegration Study (TAOS) using the Osseoanchored Prosthesis for the Rehabilitation of Amputees (OPRA) device, and the Transfemoral Amputee Osseointegration Study (TFAOS), are both underway. The TFAOS uses the OPRA implant.

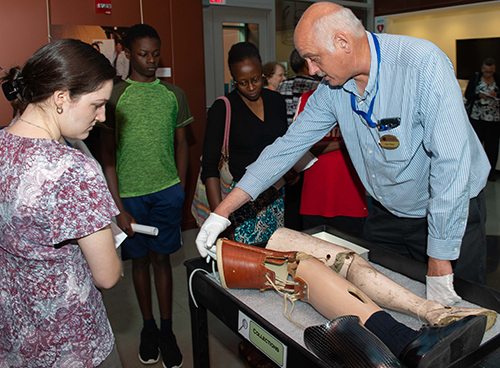

Forsberg showed the audience a Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved OPRA sample from the Walter Reed trial. It consists of three parts: the fixture that goes into the bone, the abutment that comes out through the skin, and the abutment screw. In stage one osseointegration, surgeons insert the fixture, and the end of the bone is grafted. The second stage involves arranging the soft tissues, abutment placement, and tightening the screw. A skin graft then gets sewn to the end of the bone, to ensure rigid attachment. Plastic surgeons reassign nerves that once controlled the arm and the hand. Reassigning existing nerves enables patients who have had amputations to control their prosthetic devices by thinking about the action they want to perform. True osseointegration takes several months with both implants.

A TFAOS study participant, former Army Sgt. Nick Koulchar, also attended the event and answered audience questions. Koulchar, who lost his legs to an improvised explosive device while serving in Iraq in 2008, explained, "This [osseointegration] has changed my life immensely in a very short period of time." Koulchar also noted his wheelchair dependency for nine years.

"Nick is living proof of what [osseointegration] can do," Forsberg said.

"Dr. Forsberg's work represents a significant paradigm shift in how the DoD provides for the rehabilitation of service members," explained Alan Hawk, NMHM historical collections manager. "During the Civil War, the Department of the Army purchased artificial limbs for service members who sustained amputations from combat. The museum manages a collection of examples of artificial limbs, as well as an example of the socket lining, from the Civil War. Our exhibits include examples of 19th and 20th century artificial limbs with sockets carefully carved from wood, and 21st century examples made from composite materials. In all cases, the principle was the same, so the wearer suffered from skin abrasions and the changing shape of the stump over time. Applying lessons learned from the implantation of joint prosthetics, Dr. Forsberg, by connecting to bone rather than soft tissue, completely changes how artificial limbs are constructed and promises a revolution in the rehabilitation of our wounded warriors."

"Dr. Forsberg's presentation about the research and use of osseointegration to help wounded service members recover from their injuries allowed the museum to share how innovation in military medicine actively responds to the needs of today's warfighters," stated Andrea Schierkolk, NMHM public programs manager.

NMHM's Medical Museum Science Cafés provide forums for informal talks that connect the mission of the Department of Defense museum with the public. NMHM was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 and is a division of the Defense Health Agency Research and Development Directorate. For more information on upcoming events, call 301-319-3303 or visit www.medicalmuseum.mil.