Emerging Traumatic Brain Injury Assessment Tools Show Promise for Military Medicine's Future

By Lauren Bigge

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

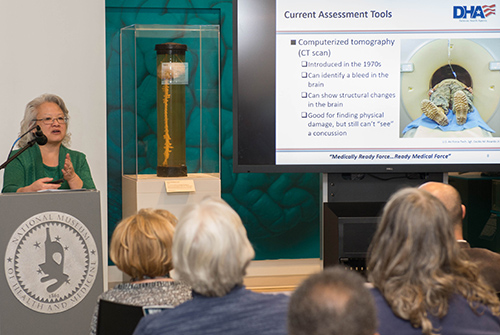

Experts from the Department of Defense (DoD) Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC) came to the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) on March 27 to share the future of assessing brain injury with the Medical Museum Science Café audience. During March each year, the DoD recognizes Brain Injury Awareness Month, and NMHM, a DoD medical museum and a division of the Defense Health Agency, offered the science café program to share the value of military medicine's contributions to the issue of traumatic brain injury prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation.

Lisa Moy Martin, Rn-BC, MA and Edison Wong, MD explained that while all military conflicts have produced traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), there are currently a number of promising assessment tools available, and ocular tools undergoing testing as well as imaging and electronic tools intended for measurements in the brain.

"A traumatic brain injury is not a new phenomenon," Martin said. "The military has advanced traumatic brain injury research because it's a way to understand the pathology and outcomes."

A TBI results from an injury in which there is an alteration of consciousness. It may be a closed injury or an open, penetrating injury. TBIs are classified as severe, moderate, or mild as in the case of a concussion. Historically, people suffering from TBIs would die due to such factors as fluid loss and limb loss. Advances in care have enabled increased survival rates. Service members evacuated quickly from battle in Iraq and Afghanistan had brain screenings early post-injury.

Martin noted that initial clinical assessments are important. A Glasgow Coma Scale measures the ability to speak, move, and open the eyes after a brain injury. Loss of consciousness and memory issues are also measured. Speech and language tests, neurocognitive tests, and electroencephalography (EEG) may be used. A patient could be tested on how fast he or she can process information, for example. "Sometimes you're given a scenario," she said. "Depending on how you answer that, it sometimes can tell whether you're really thinking clearly, or if you're not."

X-rays or Computerized Tomography (CT) scans are not as effective in detecting a TBI as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). "An X-ray can show a fracture of your skull or it can show a bullet in your head, or fragments of a bullet, but it can't see whether you have a bleed," Martin said. "A CT scan can show a bigger bleed; that's at least a moderate brain injury. It can show structural damage. It can't show tissues of the brain." An MRI can detect smaller bleeds that are not detected by a CT scan, however MRIs are not generally used due to time and expense.

Neurocognitive assessment tests (NCATs) are commonly used in the military and are being improved to make them portable and rapidly-deployable. "In the last 10 years we have come a long way," she said. "Right now, only a clinician can diagnose concussion."

Ocular assessments are currently undergoing testing; some are promising because they have the ability to assess and locate the site of a TBI. Examples of imaging and electronic tools that have assessment potential include: a portable EEG, which measures electrical activity in the brain; a near-infrared spectroscopy device, which looks at blood clots as well as small changes in blood flow patterns; and a portable transcranial doppler ultrasonograph, which measures blood clots. However, a brain with a concussion doesn't necessarily have a clot or a bleed. "Proper assessment will probably always require a combination of tests," Wong said.

Two such assessment devices are included in the collections at NMHM. One is the Eye-Sync, virtual-reality goggles that test for subtle attention problems. The other, the Infrascanner Model 2000, a near-infrared system to detect brain hematomas, is on display in the museum's TBI exhibit in the Anatomy and Pathology gallery. The exhibit showcases actual human brain specimens that demonstrate a variety of brain injuries including hemorrhages, blunt force trauma, sharp force trauma, and concussion.

A goal for the future of TBI assessment is identifying best treatments for patients, which includes medications that work for certain individuals. This concept is known as precision medicine. "PTSD [which is post-traumatic stress disorder] accompanies concussions in the military," Wong said. "It can be even more of a factor than a concussion. We have found with patients with traumatic brain injury and PTSD conditions, if they are treated appropriately for the PTSD symptoms, their concussions seem to improve better or faster. PTSD can slow down the recovery of warfighters."

"As home to one of the world's largest and most comprehensive brain collections, the National Museum of Health and Medicine, part of the Defense Health Agency's Research and Development Directorate, provides both research resources as well as exhibits and public programs that amplify our understanding of the brain and traumatic brain injury," said Andrea Schierkolk, NMHM public programs manager.

NMHM's Medical Museum Science Cafés are a regular series of informal talks that connect the mission of the Department of Defense museum with the public. The NMHM was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 and is a division of the Defense Health Agency Research and Development Directorate. For more information on upcoming events, call 301-319-3303 or visit www.medicalmuseum.mil.