Groundbreaking X-ray Imaging Technologies Enable Revolutionary Therapies For Injury and Disease

By Lauren Bigge

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

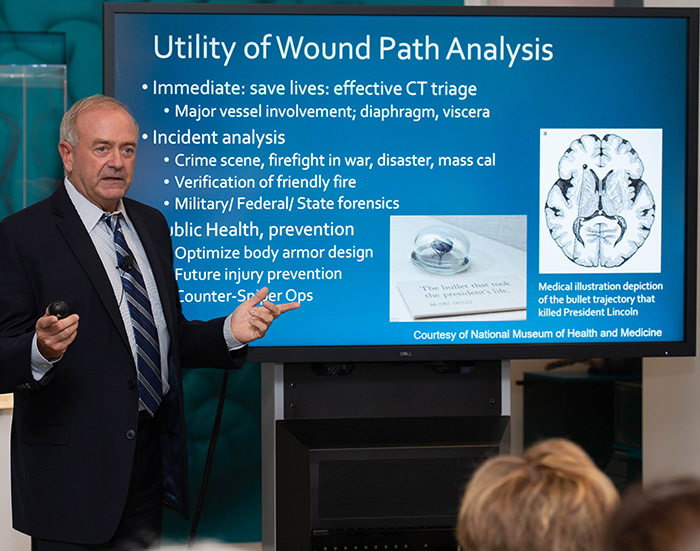

Dr. Les Folio, lead CT radiologist at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, speaks about how wound path analysis saves lives during his Sept. 25, 2018 Medical Museum Science Café presentation titled "Finding the Bullet: X-ray Imaging of Injury and Disease" at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Md. (National Museum of Health and Medicine photo by Matthew Breitbart/Released)

Technological developments in radiology stemming from wartime medical necessity have fostered groundbreaking therapies for the treatment of cancer and other diseases. That was the message Dr. Les Folio, lead radiologist in computed topography (CT) for Radiology and Imaging Sciences at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, had for Medical Museum Science Café attendees at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) on Sept. 25.

While deployed to the Middle East with the U.S. Air Force, Dr. Folio was among the first to use multi-slice CT to diagnose the wounded. He also oversaw design and construction of the imaging department at the Air Force Theater Hospital in Balad, Iraq in 2007. Using CT to analyze ballistic trajectories was crucial to making triage decisions about combat casualty care.

Dr. Folio and his colleagues focused on research questions to validate trajectory analysis. He demonstrated how ballistic trajectories analysis comes into play for triaging combat casualties and mentioned it can be used to optimize body armor design, prevent future injuries, and counter sniper operations.

He worked with radiologists and professional snipers in 2011 to field test the scientific impact of ballistics, using what he called "blast test dummies" as targets. Those CT phantoms (simulated legs) were then transferred to the NMHM's Historical Collections Division. They are featured in the "Military Medicine" gallery's Object Theater. Dr. Folio explained that the simulated legs were shot by a sniper at six different angles from a distance of 50 yards. Radiologists then identified and measured wound paths. "Radiologists could tell within 5 degrees where the shot came from," he said.

Dr. Folio recounted how he and colleagues developed the "Semi-Automated Modeling and Anatomic Reporting of Trajectories (SMART)" software to enable medical students to plot the point of bullet entry, the bullet path in the brain, and up to two ricochets. This technology addressed a common problem: the lack of personnel qualified to read CTs. SMART allowed non-radiologist physicians to plot a few points and then have the computer figure out the bullet's path. SMART, when used in a battlefield environment, could improve how medical teams treat the injured.

He also highlighted an interactive chest X-ray teaching and interpretation guide called RoboChest, which he developed for deployed military physicians. "Most chest X-rays in deployed locations were never seen by a radiologist," Dr. Folio recalled. The content follows the organization of how material is presented to medical students at the Uniformed Services University's F. Edward Hebert School of Medicine. Within two to five clicks on a computer, medical personnel in a remote clinic can match a chest X-ray image based on guidance aligned with standard teaching methods.

Dr. Folio holds several patents that resulted from technological developments in combat, including the "Relative Attenuation-Dependent Image Overlay" and the "Radiographic Marker that displays the Upright Angle in Degrees" on portable chest X-rays. The overlay enables a radiologist to view approximately 1,500 images on one combined window level instead of three times in separate window levels. The radiographic marker improves the diagnostic performance of portable chest and abdominal X-rays.

The lessons learned from the radiology aspect of military medicine translate into progress for treating cancer patients. In his current tumor trajectory research, Dr. Folio studies temporal progression over time by quantification of metastatic lesions. He showed that a metastatic tumor can be viewed in 3-dimensions and as a hologram, as he referenced his 1990 cylindrical holographic stereogram that created a multiplex hologram using 3-D surface reconstruction magnetic resonance images of a child. He transferred the stereogram to the NMHM's Historical Collections Division in 1991. Dr. Folio explained that the identification of a "target" lesion is analogous to locking on target coordinates in aviation combat when using a Doppler radar's heads-up display.

Dr. Folio mentioned he has also been working with forensic anthropologists at the National Museum of Natural History on a dry bone CT technique for archaeological-clinical comparative studies on such topics as malnutrition in South America. He noted that he imaged skeletal specimens of an 82-year-old male in the NMHM's Anatomical Collections Division for another study. "We were the first to report this way of imaging of all the bones in that kind of investigative position, in a three-dimensional sense that you can keep forever," he said. Dr. Folio's on-going interest is to examine bones for signs of disease.

Such advances in technology aid medical personnel in their ability to care for patients. They have been able to aggressively locate and treat cancerous lesions, for example, he said.

NMHM's Medical Museum Science Cafés provide forums for informal talks that connect the mission of the Department of Defense museum with the public. NMHM was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 and is a division of the Defense Health Agency Research and Development Directorate. For more information on upcoming events, call 301-319-3303 or visit www.medicalmuseum.mil.