Leg Trauma Featured in Medical Museum's World War I and 1918 Influenza Exhibit

By Lauren Bigge

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

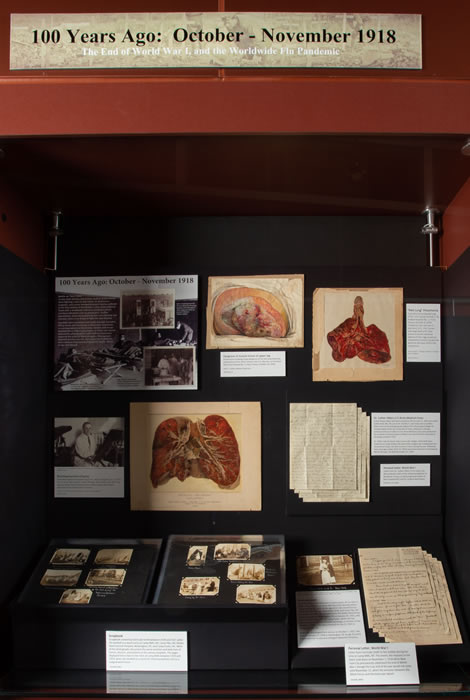

Three lower leg specimens at the National Museum of Health and Medicine (NMHM) remind the public of the sacrifices of military service members during the Great War. The specimens, showing tissue death and fractures suffered during World War I, are on display at the Department of Defense's medical museum through January 2019 in a special exhibit titled "100 Years Ago: October-November 1918; The End of World War I, and the Worldwide Flu Pandemic."

The exhibit includes three right leg specimens from service members injured in October 1918 because they tell a story of intense combat conditions, traumatic injuries, and the medical treatment that military personnel experienced during World War I.

Two specimens are from one soldier's leg; a 37-mm artillery projectile crushed the lower thigh and broke the femur and tibia. The third is from another soldier with a shattered tibia and fibula resulting from a bullet wound. Gas gangrene can be seen in the calf muscles, while signs of infection and inflammation are present in both fragments of the tibia. Both men were injured during the Meuse-Argonne offensive in France.

These examples of trauma, along with lung specimens showing the effects of bronchopneumonia from NMHM's Anatomical Collections Division, and medical illustrations, letters, and photographs from the museum's Otis Historical Archives, are being highlighted this fall to educate visitors about the personal and factual aspects of combat casualty care and the flu pandemic that coincided with the end of the Great War.

Work on the remains began in 2017 when Dr. Kristen Pearlstein, NMHM anatomical collections manager, identified several World War I-era soft tissue specimens for conservation. The remains had been preserved in semi air-tight enclosures in the museum's collections storage facility since the mid-1980s.

"The project started with a re-organization of our wet tissue specimens," Pearlstein explained. "We were consolidating the World War I specimens into one location. I found several specimens that I thought were excellent examples of trauma and had compelling background stories. We were able to identify the specimens in a book of World War I pathological conditions." She selected them for conservation based on their physical appearance, stability, and the depth of bio-historical information available in the museum's records.

The specimens are now permanently "re-housed" in fluid in custom-made acrylic casings. Anatomical laboratory specialist Juan Bassett submerged the specimens in preservative fluid, and then stabilized the remains through post-submersion maintenance. Wet tissue specimens are not frequently re-housed for display, so Pearlstein and Bassett worked to create a protocol that will allow for staff to take on future anatomical collections conservation projects with the goal that wet tissue specimens will be re-housed in a way that makes them exhibit-ready.

Collaboration with colleagues was essential and Pearlstein and Bassett knew they needed assistance handling details like acrylic shelving for additional support within the casings. Other staff members pitched in with their specialized skills and research.

Conservation efforts coincided with exhibit planning highlighting the 100-year anniversary of the end of World War I. Assistant registrar Caitlin Gilroy worked with Pearlstein and Bassett to provide space in the exhibit she was planning. "We were part of a collaborative exhibit effort," Pearlstein said. "The specimens fit in with the narrative; it is the 100-year anniversary of the injuries of these men."

Once the "100 Years Ago: October-November 1918; The End of World War I, and the Worldwide Flu Pandemic" exhibit closes, the new custom-made casings containing the leg trauma specimens will go into NMHM's ventilated cabinets designed for the long-term storage of wet tissue specimens where they can be accessed for research purposes or other exhibits in the future.

Pearlstein and Bassett look forward to taking on other conservation projects since they have achieved their vision for this one. "Now we can conserve specimens so that they are ready for exhibits," Bassett said. "This was a perfect example."