Cardiologists Search for an Improved Quality of Life with Cutting-edge Techniques and Technologies

By Jacqueline Gase

NMHM Public Affairs Coordinator

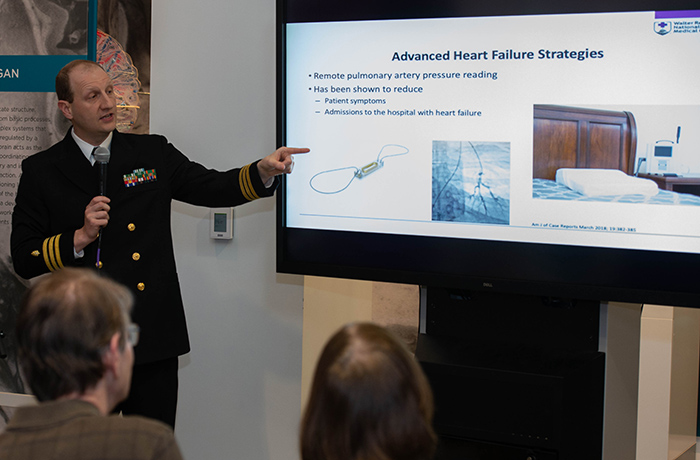

Navy Cmdr. (Dr.) Matthew Needleman, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center director of electrophysiology laboratory program and director of cardiovascular disease fellowship, speaks to the audience about electro anatomic mapping technology that reduces the need for fluoroscopy during the Feb. 26, 2019, Science Café presentation titled "Minimally Invasive Cardiology in the 21st Century" at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. (Disclosure: This image has been cropped to emphasize the subject.) (Department of Defense photo by Matthew Breitbart/ Released)

A leadless pacemaker, a left atrial appendage occluder device, a CardioMEMS monitor, and a modern ventricular assist device were among the medical innovations featured during the National Museum of Health and Medicine's Feb. 26 Medical Museum Science Café on cardiology.

Navy Commander (Dr.) Matthew Needleman, Navy Commander (Dr.) Robert Gallagher, and Navy Commander (Dr.) Michael Casey Flanagan from Walter Reed National Military Medical Center enlightened attendees on the innovative successes of minimally invasive techniques and technology in cardiology and described the use of these innovations for a better quality of life and more efficiency in cardiological care for active and veteran military service members and civilians.

Needleman, a cardiac electrophysiologist (a physician specializing in heart rhythm disorders) at Walter Reed, spoke first on the changing technology in pacemakers and electrophysiology. For a standard dual chamber pacemaker, the cardiologist will run two leads from the pacemaker through the axillary-subclavian vein, attaching one lead to the heart muscle in the right atrium and one lead to the heart muscle in the right ventricle. If a heart rhythm is abnormal, the pacemaker will register it and send electrical pulses to the heart to stabilize it. "This is a good system; this system has been around for 60 years and it works. Unfortunately, it has some limitations," Needleman said.

Delving into these various limitations, Needleman focused on how it affects service members. Infections and a required long rest period are all limiting factors, but for service members, lead fractures and lead dislodgements critically affect their duties. Both lead fractures and dislodgement can happen when there is vigorous activity. For those service members who are constantly moving, this can be a significant problem. Fractures and dislodgements don't allow the pacemaker to work properly or at all and can cause the patient to pass out, said Needleman. Also, fixing the device can be a long process, delaying the service member from their important responsibilities. Walter Reed's adoption of a leadless pacemaker resolves all these complications.

As Needleman showed an example of a leadless pacemaker, there was an audible gasp from the audience. Less than a tenth the size of a traditional pacemaker, the leadless pacemaker is no more than a few centimeters long and looks similar to a metal vitamin capsule. Due to the small size of the technology, the device is implantable through the femoral artery with a catheter and is placed directly into the right ventricle. Not only is the leadless pacemaker smaller, it is more efficient with a longer lasting battery, short recovery time, and no inpatient procedure.

Another process Needleman discussed was revolutionary electro-anatomic mapping technology that allows cardiologists to make a detailed map of a heart and identify problems without using X-ray, completely eliminating radiation exposure for patients and clinicians. As Needleman said, "The younger you are exposed to radiation the higher your risk of lifetime cancer. This is really important for us because a lot of patients we take care of are in their teens and twenties. So minimizing radiation, especially in childhood, is really critical."

Following Needleman's lecture, Gallagher took the podium to discuss structural intervention's minimally invasive technology. An interventional cardiologist at Walter Reed, Gallagher addresses heart problems through minimally invasive methods, usually using catheters. In his discussion, Gallagher focused on procedures that treated five major cardiac issues: atrial septal defect, aortic coarctation, aortic valve stenosis, patent foramen ovale, and atrial fibrillation.

In two of the cases, atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale, Gallagher described the process to cover congenital holes that form in parts of the heart. "It used to be that this could only be fixed with open heart surgery. Fortunately, today, we've come up with ways to do it less invasively," Gallagher said. The closing of the hole in the heart is done using a catheter through the groin. The small device has two disks at each end of a small rod, the two disks end up on each side of the hole, blocking it. Implanted and left there, the body forms its own tissue around it and heals, mitigating problems like stroke and heart failure.

Aortic coarctation and aortic valve stenosis are corrected through ballooning stents and replacement valves, respectively. Specifically for aortic valve stenosis, Gallagher said, "the marquee innovation in interventional cardiology has been transcatheter aortic valve replacement." When a valve gets worn out as we age, it becomes difficult to remain flexible and to open and close to allow blood to pass from the heart to the rest of the body. In its advanced stages, Gallagher said, people have fainting spells, even heart failure, and eventually die. "Less than 50 percent of those people will survive two more years," said Gallagher. Working with a catheter, cardiologists can now, without open heart surgery, replace the valve with biological tissues. This procedure can be done in people who were candidates for surgeries, extending the lives of many patients, said Gallagher.

Detailing a case from one of his patients at Walter Reed, Gallagher emphasized the importance this technology has for the military. A 22-year-old service member came in for an unrelated injury. After a CAT scan, doctors noticed he had both an atrial septal defect, or hole in the heart, and coarctation of the aorta, or a pinched aorta. Through the use of an occulder (closure) device and a ballooning stent through a catheter, the service member was discharged the next day with two problems fixed that could have been deadly if not corrected.

All three physicians emphasized the use of minimally invasive technology and procedures to enhance quality of life. For structural interventionists and electrophysiologists like Gallagher and Needleman, minimally invasive generally refers to the adoption of techniques and technology that avoid surgery and in-patient procedure. However, in the case of the third speaker, Flanagan, advanced heart failure patients still require some invasive surgical procedures.

Heart failure results in the accumulation of fluid throughout your body, with the most common symptom being shortness of breath, which, in advanced stages, can cause the inability to lie down without feeling like you are drowning in water, Flanagan said. "Heart failure is one of the top cardiovascular diagnoses in the country. Almost 6 million patients annually get diagnosed with heart failure, and almost 15 percent of deaths in 2009 were attributed to heart failure," said Flanagan.

Aside from changes in blood pressure medication, new devices are helping patients have a better quality of life. A CardioMEMS catheter allows Flanagan to monitor the pressure in the lungs that predates symptoms. After implanting the device into the lungs through an outpatient procedure, the device transmits data from the lungs to Flanagan, which is information he uses to adjust medication. Previously, patients would have to come to the hospital to check for the presence of overloaded fluid or for a complication from a medication, Flanagan explained to the audience.

Discussing an impella device and a ventricular assist device, Flanagan said that although these procedures may not seem minimally invasive, they are strides ahead of previous technology. For the ventricular assist device, Flanagan referenced a 1966 DeBakey ventricular assist device on display at the museum. Comparing his modern device to this older model, he showed the audience that the current generation's device is much smaller and allows for better quality of life. The current ventricular assist device is surgically implanted into the heart and draws blood out, runs it through a motor, then pumps it back in through the aorta to send the blood to the rest of the body. As a battery-powered device, the patient can't go home without battery support. By attaching a battery pack to the side of the body and tunneling a power cord under the skin up to the ventricular assist device, the patient can be mobile while awaiting a heart transplant.

Flanagan referenced his own memories when explaining the device to the audience, "Well you might say to yourself, 'gee, how do you live with this,' and the answer is, actually, really well. Many patients, when I was in medical school at Temple University in Philadelphia, were up on the 7th floor on all sorts of medicines and pumps to stay alive until they got a heart transplant. They left the hospital one of two ways: they got a transplant, or they didn't. Now, that doesn't happen anymore because we can put these devices in surgically, and you can go home and live while you await a heart."

Before and after the Science Café, Historical Collections Manager Alan Hawk and Historical Collections Museum Specialist Camille Bethune-Brown showed attendees examples of historical pacemakers, including one used by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, to compare to Walter Reed's new technology. "The medical museum Science Cafés offer unique opportunities for the public to see how military medicine evolves to meet the needs of the warfighter," said Andrea Schierkolk, Public Programs Manager for NMHM, "and the collections of the museum reflect the innovations in an encyclopedic manner."

NMHM's Science Café provides forums for informal talks that connect the mission of the Department of Defense museum with the public. NMHM was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 and is a division of the Defense Health Agency Research and Development Directorate. For more information about upcoming events, call (301) 319-3303 or visit https://www.medicalmuseum.mil.