Museum's Anatomical Curator Talks Forensic Anthropology with Student for "Nifty Fifty" Series, Part of the USA Science and Engineering Festival

|

|

|

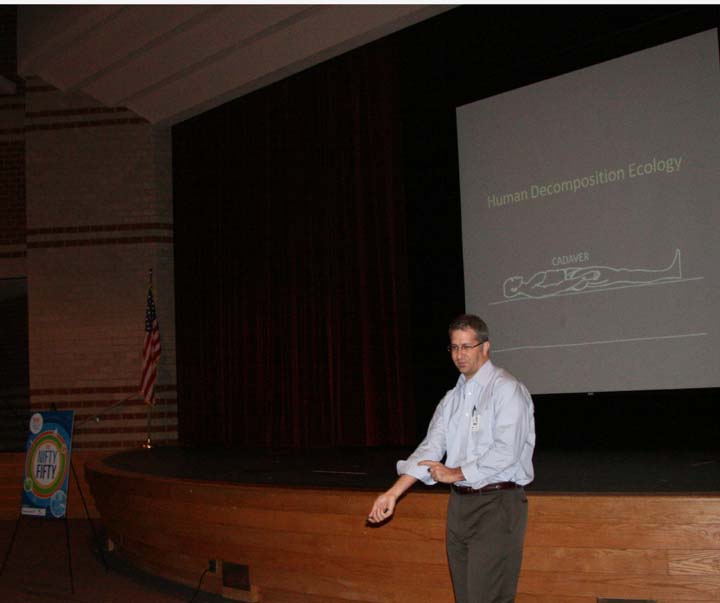

Washington, D.C.: Franklin Damann, anatomical curator for the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C., shared his knowledge of what happens to the human body after we die and the clues it can provide to forensic anthropologists with approximately 100 students at Long Reach High School in Columbia, Md. on October 8, 2010.

The talk, "Forensics Anthropology: Taphonomy and Time Since Death," was part of the "Nifty Fifty" speaker series sponsored by the USA Science & Engineering Festival, which took place on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., on October 23 and 24.

Damann, who previously served as a forensic anthropologist for the Department of Defense Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command Central Identification Laboratory in Hawaii, briefly told students about the recovery missions he led throughout Southeast Asia and northeastern China in search of missing service members from previous conflicts. He then gave an overview of the history of the fields of paleontology and taphonomy, which is the study of the processes (such as burial, decay and preservation) that affect animal and plant remains as they become fossilized, and spoke briefly about the current National Institute of Justice-funded research on human decomposition ecology and estimating time since death.

Damann said looking at the human body after death can provide information about the person and their environment. He said even when few skeletal or bodily remains are found; it is a forensic anthropologist's job to make a determination of who that person was; how long they have been dead; etc.

"There are 206 bones in the human body, right?" Damann said. "So what happens to those 206 bones that leads to five or six bones getting discovered 40 to 50 years later?"

He said human decomposition is dependent on the environment; how that person was interred; the decomposer community, such as insects and animals; the number of bacterial cells in the body; and more. Damann said. He also shared case studies with students, which depicted bodies in the process of decomposition. One body, for example, was left to naturally decompose for seven days in July at the University of Tennessee Anthropology Research Facility. Damann said this was done to answer the question, "What is the normal pattern of human decomposition?"

Erin Radebe, a chemistry and forensics teacher at Long Reach High School, said Damann's talk really brought forensic anthropology alive for students.

"I think it was an awesome opportunity to bring the field of forensic anthropology to our school so our students could connect what they're learning in the classroom to what actually happens in real life," said Erin Radebe, a chemistry and forensics teacher at Long Reach High School.

Damann said he enjoyed speaking to students and letting them know a little more about what he does.

"Being able to participate in the USA Science & Engineering Festival provided a wonderful opportunity to speak with young students in order to promote scientific investigation and to demonstrate real-world applications of science."

Related Links: