Innovations in Repair, Facial Reconstruction, Surgical Response, Protection, Research, Transportation, Rehabilitation

Military Medicine: Challenges and Innovations

During times of war and times of peace, American military medical personnel have cared for service men and women with skill and compassion. But new weapons and new environments bring new injuries, and epidemic disease remains a foe uniting all eras of combat. The unwavering commitment of military personnel to provide the best care in difficult and dire conditions, often on an enormous scale and at a fast pace, has led to major medical breakthroughs, improving the lives of people around the world.

U.S. Army Paralympics sprinter Sgt. Jerrod Fields works out at the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, California. (U.S. Army photo by Tim Hipps, IMCOM Public Affairs)

Today, an injured American service member who arrives alive at a military treatment facility is almost certain to survive. That remarkable accomplishment is the result of decades of cumulative innovation by men and women who have devoted their lives to providing combatants with the best medical care in the world.

These ongoing advances prevent and treat disease and injury, relieve suffering, evacuate combatants rapidly and comfortably, restore quality of life, and provide aid at every level through effective organizational planning.

History demonstrates that U.S. military medical personnel will continue to develop ingenious solutions to meet as yet unknown challenges.

The most solemn responsibility of the military medical system is to protect the men and women who risk their lives to defend their fellow citizens. Combatants must be protected not only against the different types of weapons used by opposing forces, but also against infectious diseases, psychological stresses, and environmental forces such as high altitudes and extreme temperatures.

The continuing effort to counter these threats has led to medical innovations that have far-reaching benefits for many people, demonstrating the broad persistent value of military medicine.

During World War I, chemical warfare was waged with munitions such as mustard gas. This innovative French Tissot Mask, with an air canister on the back, provided improved protection. It also was more comfortable than earlier models. (NCP 011758-7)

Model 1917 Helmet

World War I soldiers called this helmet the "tin hat." It offered protection primarily from shrapnel or

debris falling from above and was therefore well-suited to the conditions of trench warfare. (M-981.00005)

Successful management of combat trauma has many similarities to civilian shock trauma or emergency medical care. These types of injuries require immediate and aggressive stabilization of the patient, followed by definitive care and treatment at higher echelon hospitals.

Combat trauma poses special risks and challenges. It often occurs in hostile environments with limited ready resources. New and more lethal weapons cause new kinds of injuries. Military medical personnel have a distinguished record of adapting to these challenges with innovative treatments and technologies. Those advances have continued to raise the effectiveness of emergency medical care.

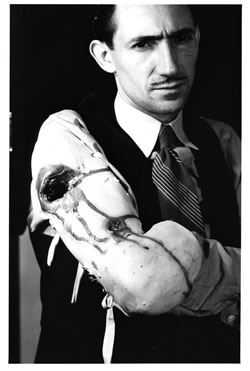

Moulages are used to train medical personnel to treat traumatic injuries. (NCP 13925)

A critical component of patient care is rehabilitation, which begins soon after injury. In order to maximize patients' potential to function, nutritional, physical and occupational therapies help wounded individuals restore their lives and redevelop lost skills.

Rehabilitation became part of the military medical program during World War I. After the war, demobilized therapists from the military found employment at the U.S. Public Health Service and Veterans Administration as well as in the civilian sector. During World War II, rehabilitation programs evolved further along with standardized equipment and procedures.

A World War I rehabilitation specialist uses a goniometer to measure the range of motion of a soldier's elbow. (OHA 353)

Specialist Corps Hat and Gloves, World War II

In 1946, Congress established the Women's Medical Specialist Corps. These gloves and hat were designed and owned

by Col. Emma Vogel, considered the founder of the Specialist Corps. The manuscript outlines Vogel's charge to

physical therapists. (M-350.00078, OHA 355)

Modern medicine and warfare have undergone simultaneous technological revolutions, the new tools of medicine keeping pace with the new devices of warfare. Sometimes the scale and pace of research have been innovations in themselves. The discoveries of antisepsis, anesthesia and imaging devices advanced all of modern medicine. But high performance in exceptionally dangerous environments has required the tools of simulation and advanced computational technologies as well as a concerted effort to learn from the trauma of combat. Even long-standing challenges benefit from on-going research, such as the development of an effective malaria vaccine and freeze dried plasma.

Only two years after their discovery, X-ray devices were used aboard the hospital ship Relief in 1898 during the Spanish American War. The rapid adoption of this technology paved the way for the rise of a medical specialty. By World War I, as many as one fourth of all military hospital admissions involved X-ray evaluations. (AMM 2186)

Copper Manikin, Chauncey

Manufactured by General Electric in the late 1940s and early 1950s, this manikin was named Chauncey by its

developers at the Harvard Fatigue Laboratory in Boston and U.S. Army Research Institute for Environmental Medicine

in Natick, Massachusetts. The manikin is made of copper that could be heated to maintain a constant skin temperature.

They used the manikin to evaluate thermal insulating properties of military garments and headgear. (2011.0054)

The use of the recruit physical on a large scale is an innovation in medical preparedness and surveillance. But when even a healthy combatant is injured, speed of intervention and continuity of care are essential. Thanks to continuing advances in organization, injured U.S. service members routinely receive this kind of intensive care. Today, a service member wounded abroad will arrive in an American hospital in a stabilized condition, in less than a week.

Recent organizational improvements ensure that injured or sick service members are removed from theater quickly and comfortably. Distances between places of injury and sources of medical care have been greatly shortened. When patients are moved from the place of injury to higher levels of care, critical care is delivered without interruption. Logistical advances further ensure that medical personnel always have the instruments, equipment, medicines, blood and supplies needed to treat their patients.

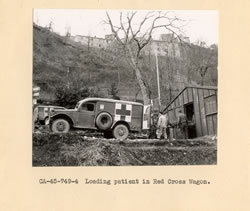

Wounded combatants are transferred from plane to ambulance during World War II. (NCP 4124)

Personal Information Carrier, late 1990s

The Personal Information Carrier is a portable electronic device designed to store the essential elements

of a service member's personal medical history so it can be readily accessed and updated by medical personnel

via laptop or hand-held computer. (M-360.10020)

Over the course of more than 200 years, surgeons and other medical professionals have relied on tools in kits like these to save lives and determine cause of death.

The diversity of instruments and kits reflects innovations in medical technology, countries of origin and the specific needs that the kits served. There are surgical, autopsy, dental, nursing and veterinary kits. Some can be worn on a belt; others must be pulled on wheels. Still others connect to vastly larger communication systems.

With the requirements of sterilization, steel and other metals replaced wood and ivory. As medical advances enabled surgeons to perform more complex procedures, surgical kits expanded greatly in sophistication.

Surgeons operate at Walter Reed General Hospital in 1957. (SC 521403)

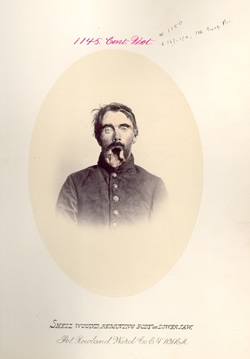

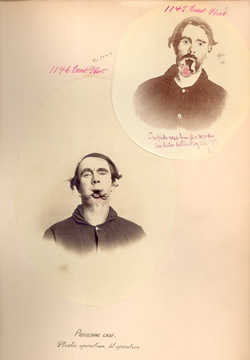

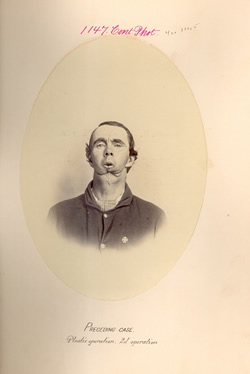

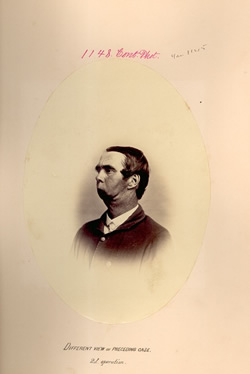

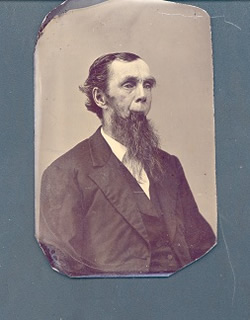

Some combatants suffer facial and skull injuries so traumatic they require the reconstruction of bone and the delicate tissues of the eyelids, nose and mouth. U.S. military surgeons and researchers have made key advances in this field of reconstruction, pioneering increasingly sophisticated and effective procedures.

As long ago as the Civil War, American military surgeons documented 30 facial reconstructions. By World War I, facial reconstruction had been indoctrinated into U.S. military medicine. Today, advances in instruments, materials and processes have dramatically improved the safety and scope of facial reconstruction. At institutions like Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, researchers and clinicians continue to develop cutting-edge technology.

These photographs show the results of a series of facial reconstructive surgeries that Pvt. Roland Ward underwent after his lower jaw was shattered during the Civil War. (CP 1145, 1146, 1147, 1148, 1150)