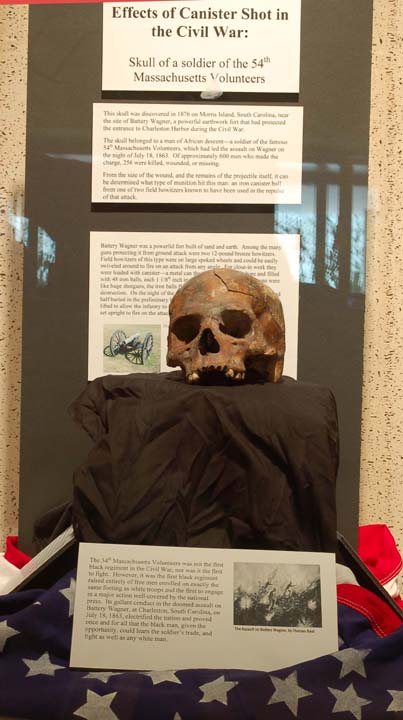

Effects of Canister Shot in the Civil War: Skull of a soldier of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers

This skull was discovered in 1876 on Morris Island, South Carolina, near the site of Battery Wagner, a powerful earthwork fort that had protected the entrance to Charleston Harbor during the Civil War.

This skull was discovered in 1876 on Morris Island, South Carolina, near the site of Battery Wagner, a powerful earthwork fort that had protected the entrance to Charleston Harbor during the Civil War.

The skull belonged to a man of African descent—a soldier of the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, which had led the assault on Wagner on the night of July 18, 1863. Of approximately 600 men who made the charge, 256 were killed, wounded, or missing.

The skull belonged to a man of African descent—a soldier of the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, which had led the assault on Wagner on the night of July 18, 1863. Of approximately 600 men who made the charge, 256 were killed, wounded, or missing.

From the size of the wound, and the remains of the projectile itself, it can be determined what type of munition hit this man: an iron canister ball from one of two field howitzers known to have been used in the repulse of that attack.

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteers was not the first black regiment in the Civil War, nor was it the first to fight. However, it was the first black regiment raised entirely of free men enrolled on exactly the same footing as white troops and the first to engage in a major action well-covered by the national press. Its gallant conduct in the doomed assault on Battery Wagner, at Charleston, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863, electrified the nation and proved once and for all that the black man, given the opportunity, could learn the soldier’s trade, and fight as well as any white man.

The 54th Massachusetts Volunteers was not the first black regiment in the Civil War, nor was it the first to fight. However, it was the first black regiment raised entirely of free men enrolled on exactly the same footing as white troops and the first to engage in a major action well-covered by the national press. Its gallant conduct in the doomed assault on Battery Wagner, at Charleston, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863, electrified the nation and proved once and for all that the black man, given the opportunity, could learn the soldier’s trade, and fight as well as any white man.

The Assault on Battery Wagner

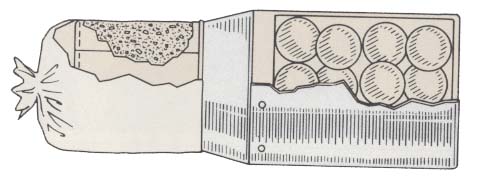

Battery Wagner was a powerful fort built of sand and earth. Among the many guns protecting it from ground attack were two 12-pound bronze howitzers. Field howitzers of this type were on large spoked wheels and could be easily swiveled around to fire on an attack from any angle. For close-in work they were loaded with canister—a metal can the size of the cannon-bore and filled with 48 iron balls, each 1 1/8th inch in diameter. When fired, these guns were like huge shotguns, the iron balls flying off in a wide arc of death and destruction. On the night of the assault, both howitzers were knocked out and half buried in the preliminary bombardment of the fort, but once the barrage lifted to allow the infantry to attack, they were easily dug out of the sand and set upright to fire on the attacking forces.

Approximately 600 men of the 54th Massachusetts made the assault on Wagner. Due to tidal flooding of the ground in front of the fort, the regiment was pressed to its extreme right. This movement also took them out of the line of fire of most of the big guns of the fort. Directly ahead was the highest portion of the fort, though unbeknownst to the attackers, almost totally undefended, as the Confederate regiment to be posted there refused to leave the safety of their bomb-proofs. Had the 54th charged straight ahead, it would have been up and over and right into the heart of the fort. Unfortunately, commander Colonel Robert G. Shaw led the regiment to the left, against the lower, but heavily defended, center of the wall. Besides the four 32-pounders directly ahead, the mass of attacking men was subject to enfilading fire from the two recovered field howitzers above them. The regiment clung to the face of the fort for almost an hour, but eventually had to retire. Approximately 6000 more Union troops eventually were thrown into the battle to no avail. Wagner remained in Confederate hands for another four months, then was evacuated when its purpose had been achieved.

The skull on display shows the destructive effect of the 12-pound canister used in the Fort's defense. When the gun was fired, the individual balls in the canister round jostled and bumped into each other and so exited the barrel at relatively low velocity. In this case, it can be seen that a single ball has created a nearly round entry wound and then incompletely penetrated the opposite side of the skull leaving fragments of iron next to the bone. Radiating fractures from the entrance and exit can be seen crossing the temporal, parietal and frontal bones. The ball entered from rear left, traveled back to front and upwards exiting on the right side. The entrance and exit correspond almost perfectly with the anatomical landmarks asterion and pterion respectively. The skull was exposed for approximately 16 years, along with the fragments of the rusting iron ball that stained the bone around the exit wound and darkened the entire cranium.

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.