Hairballs: Myths and Realities behind some Medical Curiosities

The National Museum of Health and Medicine has in its anatomical collection 24 veterinary and 3 human hairballs or "trichobezoars." To commemorate National Hairball Awareness Day on April 27, 2006, the museum featured a temporary display of 10 of these hairballs to explore the myths and realities behind these medical curiosities. Included were hairballs from a steer, two oxen, three cows, a calf, horse, and a chicken.

|

|

|

|

and Medicine. 1068 |

and Medicine. 1996 |

Many of the museum's veterinary specimens were collected in the late 1800s by U.S. Army surgeons and were part of the museum's comparative anatomy collection. At that time, Army Surgeons working in remote outposts who had infrequent opportunities to collect pathological materials for the museum insteadcontributed natural history specimens in order to promote the museum's mission to become a general pathology museum with examples of "all forms of injury and disease."

Every cat owner knows about hairballs—usually you "find" them in the middle of the night after you've stepped into a pile of something that looks and feels like anything but hair. Did you know that cats aren't the only ones to get hairballs? Humans and cud-chewing animals, such as cows, oxen, sheep, goats, llamas, deer, and antelopes get hairballs or other types of "bezoars" (pronounced BE-zor). A bezoar is a mass of nondigestible matter that collects in the stomach.

"Bezoar" is a Persian word that means "protection from poison," because bezoars were believed to be a universal antidote against poisoning. Bezoars from wild goats, antelopes, and other cud-chewing animals of Persia were introduced to Europe in the 11th century where they were popular in medicinal remedies until the 18 century. In China, ground-up cow bezoars have been used as medicine for more than 2,000 years, particularly to treat diseases of the mouth.

There are four types of bezoars:

- Lactobezoar: a mass of undigested milk, most commonly found in pre-term infants on highly concentrated formula

- Trichobezoar: a mass of hair

- Phytobezoar: a mass of undigested food particles usually from fruits and vegetables such as celery, citrus fruits, coconut, pumpkins, grape skins, prunes, raisins, and most notably persimmons (bezoars resulting from persimmons are called diospyrobezoars)

- Pharmacobezoar: a mass of medications such as extended release medicines or bulk-forming laxatives

|

|

|

|

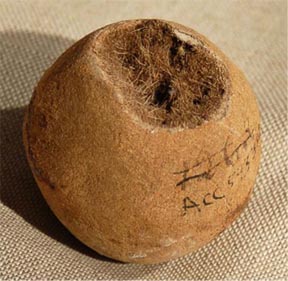

Bezoar from a cow

National Museum of Health and Medicine.543342 |

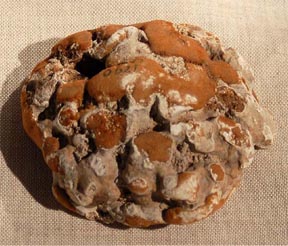

Bezoar from a calf

National Museum of Health and Medicine. 1290 |

Many of the hairballs in the museum's collection are from cows. Cattle are susceptible to getting hairballs in their stomachs because they do not vomit. Cows with hairballs become emaciated, eat little grass, and drink lots of water. Cow hairballs can grow quite large and are usually found after death.

An unusual hairball was contributed in 1897 by a Washington, D.C. resident who removed it from the craw of a young chicken. The chicken was a pet and associated with a dog for which it had formed a strong attachment. It picked the hair from the dog, supposedly because there was no grass accessible. The chicken had been unable to eat for several days and was threatened with starvation. The owner surgically removed the hairball, and the chicken survived.

|

|

||

|

Bezoar from the craw of a chicken

National Museum of Health and Medicine 543344 |

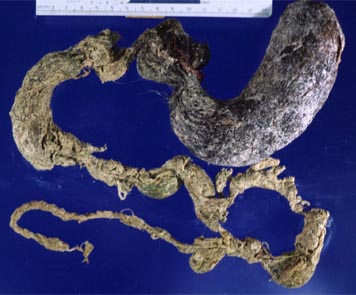

Bezoar from a human, National Museum of

Health and Medicine. AFIP 1126060 |

Human hairballs occur most often in children and young women who have mental disorders such as trichotillomania (chronic hair pulling) or pica (compulsive cravings to eat nonfood items). One of these is permanently on display in the museum's "Human Body/Human Being" exhibit. It was removed successfully from the stomach of a 12-year-old girl whose parents claimed she had been eating her hair since the age of 6. The hairball was removed surgically, and the girl survived.

|

|

||

|

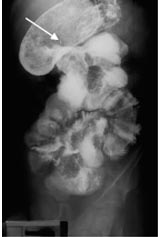

Rapunzel syndrome (trichobezoar)

Image courtesy of Department of Radiology, AFIP 2824793 |

Rapunzel syndrome (trichobezoar)

Image courtesy Department of Radiology, AFIP 2621591 |

Bezoars are rare in people with a normal digestive tract, but occur more often in adults with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, cystic fibrosis, renal failure, vagotomy, or partial gastric resection. Some illnesses, such as diabetes, can slow stomach motility. The shape of the stomach and the narrow opening of the pyloric sphincter contribute to the tendency of food and objects to collect in this area rather than to pass into the duodenum.

Rarely trichobezoars extend beyond the stomach into the bowel (a condition known as Rapunzel syndrome). Often they are difficult to diagnose, but some symptoms include cramps, bloating, loss of appetite, weight loss, and bad breath. The method for removing bezoars depends on the type. Most trichobezoars must be removed surgically, since the twisted strands of hair become wire-like and can perforate the stomach. Some phytobezoars can be dissolved with enzymes or broken down with endoscopy.

Sources and Additional Reading:

Sanders, Michael K. "Bezoars: From Mystical Charms to Medical and Nutritional Management. The Practical Gastroenterolgy Journal (January 2004). http://www.medicine.virginia.edu/clinical/departments/medicine/divisions/digestive-health/nutrition-support-team/nutrition-articles/practicalgasto1.04.pdf (Accessed 5/1/06).

"Bezoars and Foreign Bodies," The Merck Manual of Medical Information –Second Home Addition (Last revised February 1, 2003) http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/bezoars-and-foreign-bodies/bezoars (Accessed 5/1/06).

Credits:

Curation:

Lenore Barbian, Ph.D.

Andrea Schierkolk

Special Thanks:

Ellen Chung, LTC, MC, USA, Radiology, AFIP

Bill Discher

Steve Hill

Angela Levy, COL, MC, USA, GI Section Chief, Radiology, AFIP

Web Development and Publicity:

Steven Solomon

Courtney MacGregor

Virginia McMillan

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.