Walt Whitman's Soldiers

“I go around among these sights, among the crowded hospitals doing what I can, yet it is a mere drop in the bucket. . .the path I follow, I suppose I may say, is my own.” ~ Walt Whitman, Drum Taps

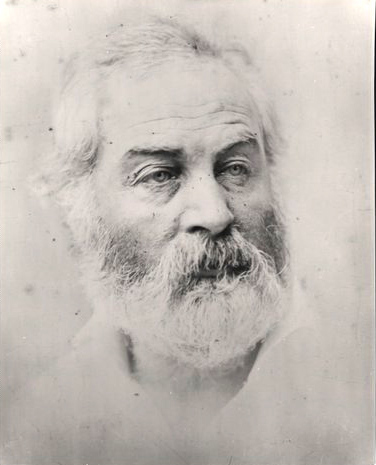

The National Museum of Health and Medicine holds several photos and unique anatomical specimens that open a window onto Walt Whitman’s life and his experiences in Washington’s Civil War hospitals.

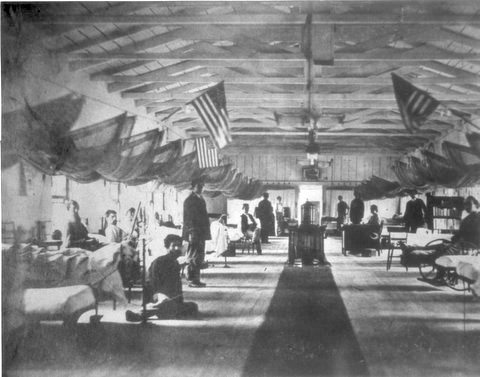

These images and artifacts connect us not only to Whitman, who lived and worked in Washington from 1863 to 1873, but also to the soldiers he nursed and to the makeshift institutions where, as Whitman wrote, “every cot had its history.” Inspired by his witness of suffering by soldiers and of caregiving by nurses and doctors, Whitman’s writings from this tumultuous period stand among his greatest.

Walt Whitman came to Washington in 1863 in search of his brother, George, whose name Whitman and his family saw listed on a newspaper casualty roster from the battlefield at Fredericksburg, Virginia. After searching for George in nearly forty Washington hospitals, Whitman travelled to Fredericksburg to find George’s unit. There, he found George alive and having suffered a superficial facial wound. However, Whitman’s personal relief quickly turned to horror as he witnessed the human costs of battle.“I notice a heap of amputated feet, legs, arms, hands, &c., a full load for a one-horse cart, human fragments, cut, bloody, black and blue, swelled and sickening.” Whitman’s experiences at war profoundly shaped his own psyche and his poetic vision. He sought to make sense of the personal and national trauma of the Civil War while devoting himself to visiting wounded soldiers in Washington’s hospitals.

National Museum of Health and Medicine CP 2241.

Whitman visited Armory Square Hospital more frequently than any other hospital in the city. Located at the end of Seventh Street SW and near the Washington and Alexandria Railroad, this institution offered care to the most serious cases returned from the Virginia battlefields. Here, as in other hospitals around the city, Whitman nursed soldiers by writing down their stories, writing letters giving them small gifts, holding them, and comforting them through conversation. His purpose, he wrote, was "just to help cheer and change a little the monotony of their sickness and confinement.”

“I hear the tramp of armies, I hear the challenging sentry . . . Surgeons operating, attendants holding lights, the smell of ether,the odor of blood.” ~ Walt Whitman, Drum Taps

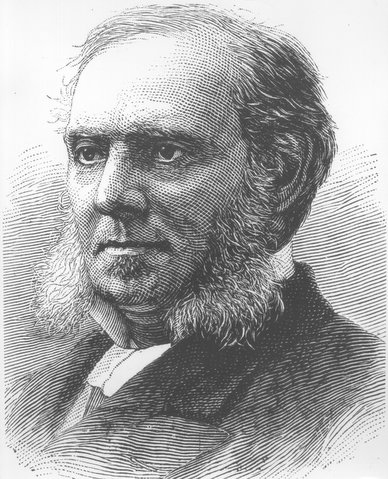

At Armory Square, Whitman observed the work of Dr. D. Willard Bliss, the chief surgeon, whom Whitman described in Specimen Days as “one of the best surgeons in the army.” After the war, Bliss praised Whitman for his service to the nation’s soldiers. “No one person who assisted in the hospitals during the war accomplished so much good to the soldier and for the Government as Mr. Whitman.” In 1881, Bliss became the attending physician to President James Garfield when he was shot by Charles Guiteau.