With the space race in full swing during the early 1960s, American scientists were determined to be the first to send a person to the moon. But first, they had to answer several important questions. Spacecraft were designed to run on autopilot, but what if the operating systems failed? Could a human carry out tasks during launch, the state of antigravity, and re-entry?

Before sending a person into space, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) trained several chimpanzees to participate in flight simulations. One of these chimps, "Number 65" was nicknamed HAM by his handlers. HAM is an acronym for the laboratory that trained him for his historic mission: the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico.

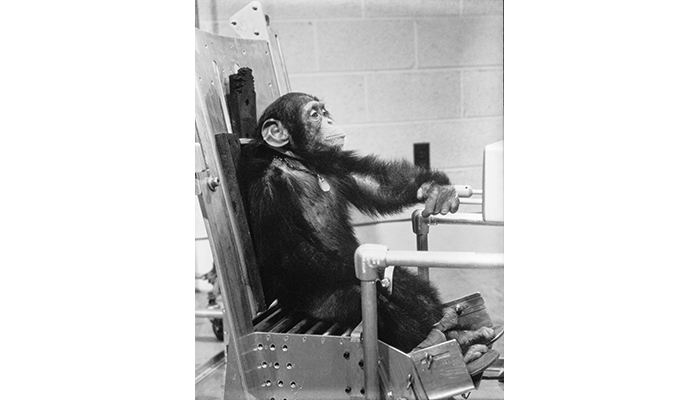

Chimpanzee HAM during preflight activity prior to the Mercury-Redstone 2 test flight. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

U.S. Army Colonel (Ret.) Joseph V. Brady, a behavioral neuroscientist with the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, collaborated with NASA to train HAM the chimp to operate a system of lights and levers, instructing him to flip at least one lever every twenty seconds to avoid an electrical shock to his foot. His reward for success was his favorite snack, banana pellets.

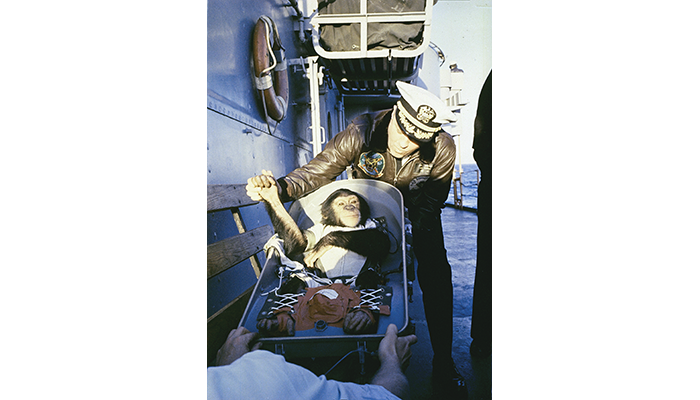

HAM was the first chimp in space as he blasted off to an altitude of 157 miles during the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission on January 31, 1961. He performed the tasks that he was trained to do and was found to be in good health after recovery from the flight, despite some fatigue and dehydration. Just three months later, on May 5, Commander Alan B. Shepard, Jr., a Navy astronaut, piloted the Mercury capsule on America's first human suborbital flight.

Chimpanzee HAM is greeted by the recovery ship commander after returning from his flight on the Mercury Redstone rocket. (Photo courtesy of NASA)

HAM retired from research in 1963 and lived for almost twenty years at the Smithsonian's National Zoo in Washington, D.C. before he was transferred in 1980 to the North Carolina Zoological Park. HAM lived his final days with a small colony of chimpanzees there and died January 19, 1983 at 26 years as a result of chronic heart and liver disease.

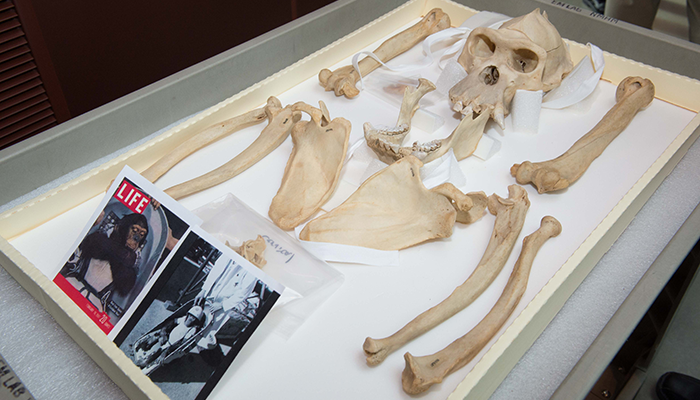

The space chimp HAM on display during the June 23, 2015, Medical Museum Science Café at the National Museum of Health and Medicine. HAM's flight led directly to astronaut Alan Shepard's first human suborbital flight in May 1961. (150623-A-MP902-004: NMHM photo)

HAM's remains were sent to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington, D.C. for necropsy. It was determined that he did not suffer any long-term effects from space flight. However, a controversy arose over what to do with HAM's remains. There was talk of preserving him in the Great Ape House at the Smithsonian National Zoo. This resulted in a public outcry about death without dignity. In fact, a sophomore from West High School in Painted Post, New York, wrote that she was shocked that HAM would be "stuffed and displayed," and she added, "A chimpanzee is not a green pepper."

Full anatomical skeleton of chimpanzee HAM, photographed at the National Museum of Health and Medicine. [AFIP 1871496: NMHM photo]

In 1983, HAM's soft tissue and hide were buried at the International Space Hall of Fame in Alamogordo, New Mexico, and his skeleton was entrusted to the Anatomical Collections at the National Museum of Health and Medicine, where it is cared for today.

References

Henry, J.P.: Synopsis of the Results of the MR-2 and MA-5 Flights, Results of the Project Mercury Ballistic and Orbital Chimpanzee Flights, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, SP-39, 1963.

Gray, T.: Animals in Space. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, August 2, 2004.

http://history.nasa.gov/animals.html

Relevant Links:

Brady, Joseph V. Behavior Analysis in the Space Age. Behavior Analyst Today, 8(4), 398-412.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0100640

Hanser, Kathleen: Mercury Primate Capsule and Ham the Astrochimp, November 10, 2015.

https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/mercury-primate-capsule-and-ham-astrochimp

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.