This year on December 25, the National Museum of Health and Medicine celebrates the birthday of Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) and his work on optics and color. Decades ago, NMHM was the grateful recipient of a second edition of Newton's Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light (1718). Like the first edition, originally published in English in 1704 and in Latin two years later, the second edition included Newton's mature thoughts about color and the nature of light; Newton, long since a member of the Royal society, had considered both for more than three decades of his life as a natural philosopher, dating to his earliest Cambridge lectures. His writings influenced, if not definitively characterized, how we have framed questions about the behavior of light ever since.

NMHM received the work, replete with hand annotations, as part of a gift of objects from the American Ophthalmologic Society and historian of ophthalmology Burton Chance, MD, over several years in the late 1930s. All the objects related to the evaluation of human vision, and some to the assessment of sensitivity of color vision in humans, which was of particular interest to Dr. Chance, who came from a family with colorblind members who were sea captains. The ability to appreciate color is key to vision evaluation in the military–for target recognition, for instance; hence, the collection is of value in understanding how color vision is tested even now.

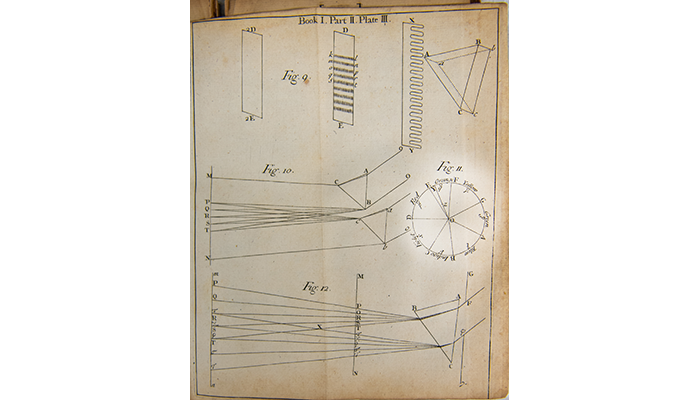

Page from Opticks, 2nd ed., 1718, Book I, Part II, Plate 3. In figure 11, Newton diagrammed his color circle. (Accession 58961) (191216-D-D0458-0002: NMHM photo illustration)

Opticks remains one of the most important contributions to science and it details careful experimentation on color by Newton. Using prisms, Newton was able to separate the previously thought to be "pure" light of sunshine into a spectrum of visible hues and studied the refrangibility (refractibility) of each color as well as sunlight itself. From these studies, he conceived of what is thought to be the first spectral "color circle" by creating a closed figure joining the ends of the linear visible spectrum. How many colors were distinct enough to occupy specific, if not precisely equal, areas of that circle? Ultimately, and after significant consideration, Newton settled on seven. Scholars link that number seven to other realms of enumerated phenomena in his day–seven planets, seven musical tones; Newton may have done so as well, driving him to identify seven hues.

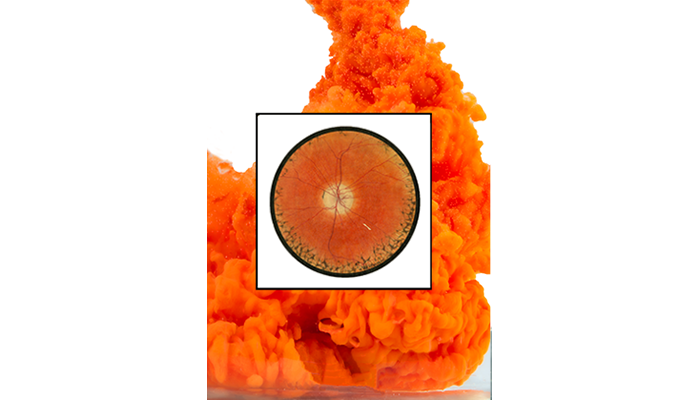

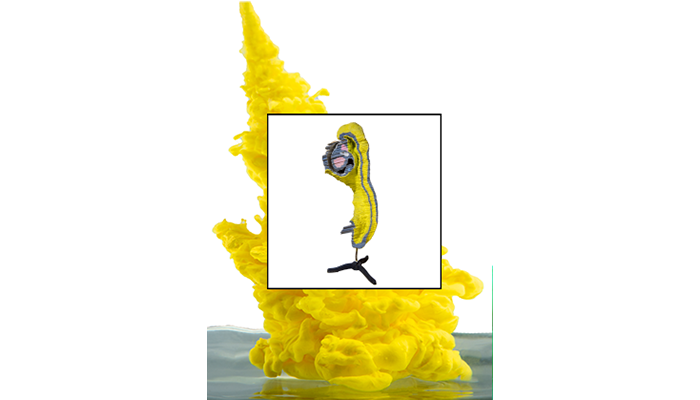

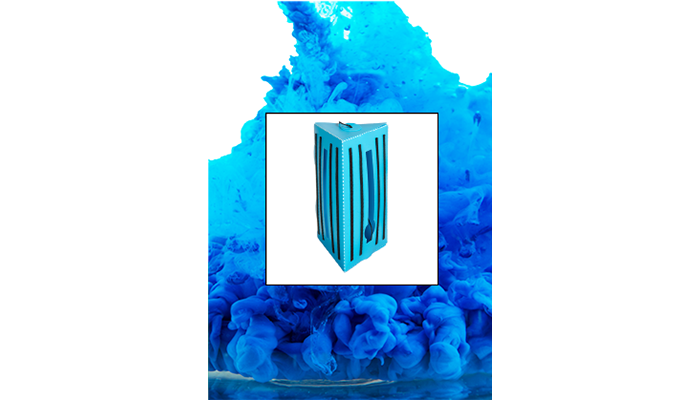

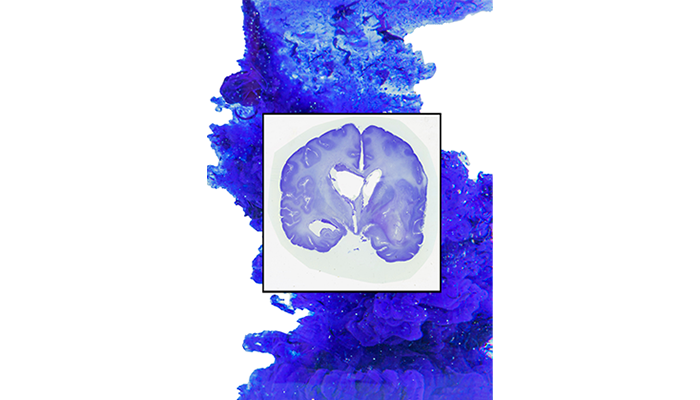

But which colors were distinct enough to occupy areas of the circle: the now familiar red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet--Roy G. Biv. In the images below, NMHM staff selected seven items from the museum's collections, each representing one station on Newton's circle of colors.

Thank you to Ian Herbst, Laura Cutter, Andrea Schierkolk, and Jacqueline Gase for their contributions to this article.

Resources

Keeney, A.H. "Burton Chance, Sr., MD, 1868-1965." American Journal of Ophthalmology 59, no. 6 (June 1965): 1147-1148.

Kuehni, R.G. Color Space and Its Divisions: Color Order from Antiquity to the Present. Hoboken NJ: Wiley Interscience, 2003, 44-5

Pesic, P. Music and the Making of Modern Science. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2014, 124-5.

Relevant Links:

Newton Shows the Light: A Commentary on Newton (1672) 'A Letter…Containing his New Theory About Light and Colours…'

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4360081/

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.