Maj. Dwight Harken wrote in a letter to his wife during August 1944:

"Now for the statistics that I almost hate to breathe because it cannot be very much longer. In spite of a tremendous number of patients that have come under our care and for very major things – to wit three foreign bodies in the heart within three days etc. – we have not yet had a death in the chest service. I almost hate to speak of this for it is much too good to last."

In May 1944, Maj. Dwight Harken was tasked with founding a chest surgical center as part of the 160th General Hospital in Cirencester, Gloucestershire, United Kingdom. Prior to World War II, heart surgery was rarely performed because the patient was unlikely to survive the procedure. However, the only thing more risky than heart surgery was not treating the condition necessitating the procedure.

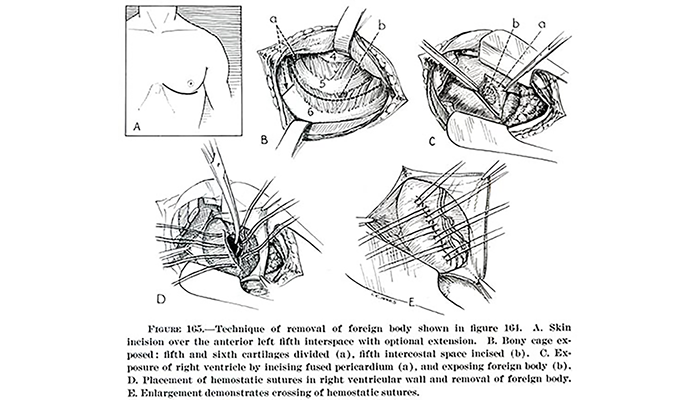

Diagram showing the technique for the removal of foreign bodies from the heart in Dwight E. Harken's article Management of Retained Foreign Bodies in the Heart and Great Vessels, European Theater of Operations.

On June 10, 1944 (D-Day plus four days), the first of 982 combat thoracic casualties began arriving and surgical operations commenced. Surgeons cutting into a beating heart had to be calm, precise, and efficient. First, the surgeon X-rayed the patient to identify the location of the foreign body to be removed. The first cut into the chest was between the ribs to expose the heart. Sutures were placed into the heart muscle prior to making an incision. After 15 to 20 seconds, the surgeons cut into the heart, located and extracted the foreign body, and pulled the sutures tight to seal the opening. Upon removal, the foreign body was taped to the patient's hand so he could keep it as a souvenir. A patient could lose up to a liter of blood (one-fifth of their total blood volume) during a procedure that could last up to one-and-one-half hours.

Photograph of heart surgery during World War II shows the appearance of heart at instant of incision into right ventricle. (Image courtesy of OTSG-USA)

In a letter to his wife in June 1944, Harken described one of his cases: "For a moment, I stood with my clamp on the fragment that was inside the heart, and the heart was not bleeding. Then, suddenly, with a pop as if a champagne cork had been drawn, the fragment jumped out of the ventricle, forced by the pressure within the chamber. …Blood poured out in a torrent. …I told the first and second assistants to cross the sutures and put my finger over the awful leak. The torrent slowed, stopped, and with my finger in situ, I took large needles with silk and began passing them through the muscle wall, under my finger and out the other side. With four of these in, I slowly removed my finger as one after another was tied. The only moment of panic was when we discovered that one suture had gone through the glove on the finger that had stemmed the flood. I was sutured to the wall of the heart! We cut the glove and I got loose."

Harken performed surgery on 138 patients. Of those, two had foreign bodies that could not be extracted, and two more had foreign bodies where removal was deemed an unjustifiable risk to the patient. In addition to the 138 patients, 15 other patients were not operated upon, and the foreign body was left in place. Harken's heart surgeries yielded an unprecedented success rate. All of the patients recovered completely from their wounds, and Harken proved that heart surgery was a viable course of action.

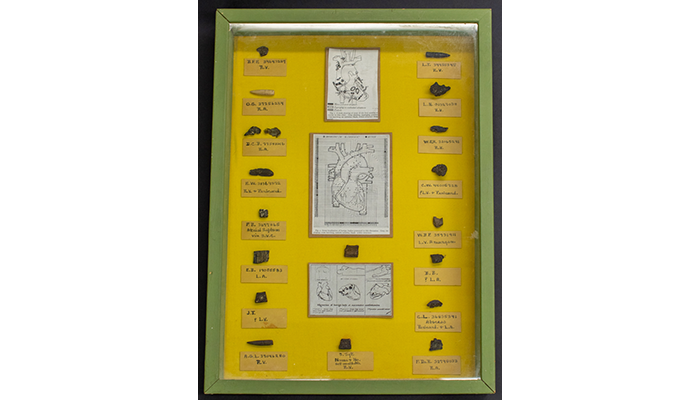

This shadow box created by Dwight Harken preserves some of the 134 foreign bodies extracted from patients' hearts or pericardium. (NMHM photo)

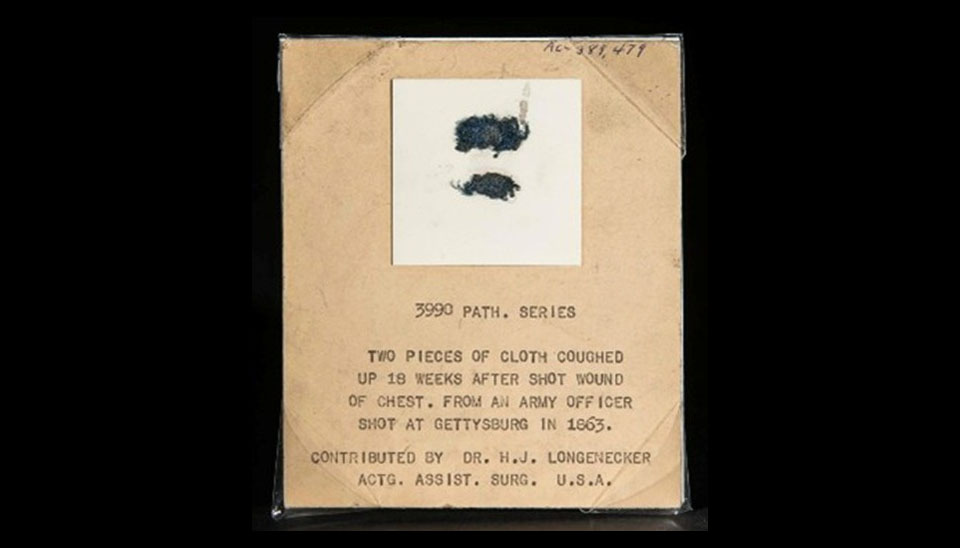

Projectiles and foreign bodies were among the items requested by Surgeon General William Hammond in his announcement establishing the Army Medical Museum in 1862. Since then, the museum has collected bullets, shrapnel, shell fragments, and more, removed from wounds sustained by service members during World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. These items, a part of the museum's Historical Collections, are valuable in the study of wound ballistics, documenting the form and the mass of the agent that lacerated the patient's body. Combined with analysis of the characteristics of the weapon, the muzzle velocity of the firearm or the explosion of the shell can provide military surgeons insight on how weapons create wounds which can be used to inform better treatment. Additionally, these foreign bodies have a greater significance as tokens kept by the wounded person as a testimony to his or her survival.

References

McRae, Donald. Every Second Counts: The Race to Transplant the First Human Heart. New York: Penguin Group, 2006.

Relevant Links:

Alivizatos, Peter A. "Dwight Emary Harken, MD, an all-American surgical giant: Pioneer cardiac surgeon, teacher, mentor." Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 31, no. 4 (Oct. 2018): 554–557.

Cooley, Denton A. "In Memoriam Dwight Emary Harken." Texas Heart Institute Journal 20, no. 4 (1993): 250–251.

Harken, Dwight E. "Management of Retained Foreign Bodies in the Heart and Great Vessels, European Theater of Operations" [Ch. VIII] in Frank B. Berry, (ed.) Medical Department, United States Army, Surgery in World War II, Thoracic Surgery Vol II. Washington: Office of the Surgeon General, 1965: 354-95.

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.