In addition to serving as a repository for artifacts and records related to President Abraham Lincoln's assassination, the National Museum of Health and Medicine, then known as the Army Medical Museum, occupied the Ford's Theatre building from 1866-1887. The theatre, which would later become an historic site, also played an important role in NMHM's institutional history.

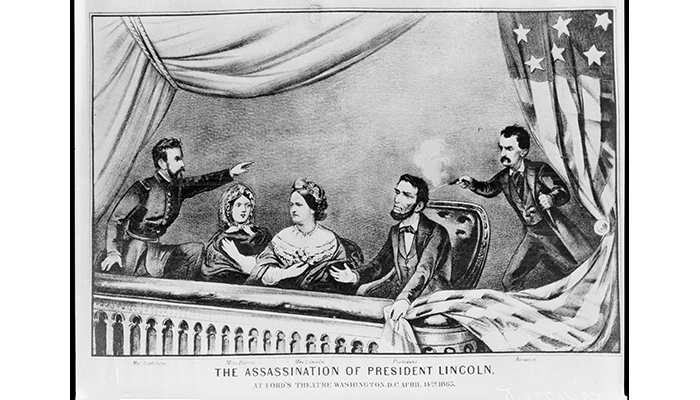

"The Assassination of President Lincoln at Ford's Theatre. Washington, D.C. April 14th, 1865." (MIS 53-10731-D)

When John Wilkes Booth shot President Lincoln at Ford's Theatre on April 14, 1865, the nation was plunged into grief. The assassination ensured that the end of the Civil War was marked by the most somber of events. The assassination and its aftermath also marked an end to Ford's Theatre, which had operated with great success and fanfare in Washington, D.C.

After the conspirators were hanged on July 7, 1865, John Ford planned to reopen his theatre. Advertising The Octoroon for the night of July 10, he sold over 200 tickets. He also received a letter threatening to burn down the theatre, should it be reopened as such. The Judge Advocate ordered the theatre to refuse admission and Ford did not attempt to open the theatre again. Starting that same month, the U.S. government leased the theatre from Ford.

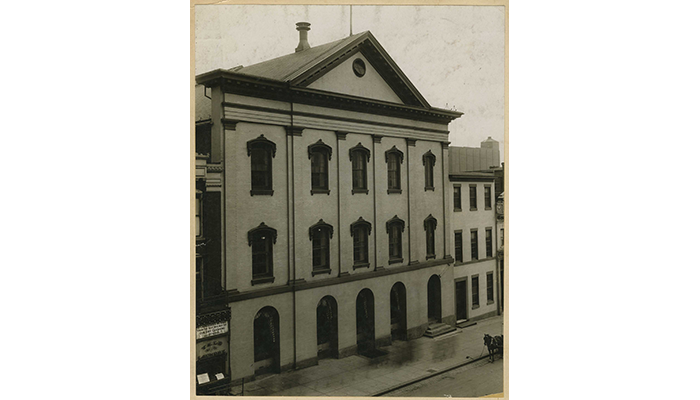

Fourth home of the Army Medical Museum at Ford's Theatre, formerly 454, now 511 10th Street, N.W. 1866. (Reeve 32782)

Almost one year later, on April 7, 1866, Congress approved the purchase of the theatre for "the deposit and safekeeping of documentary papers relative to the soldiers of the army of the United States and of the museum of the medical and surgical department of the army" [sic]. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton then assigned the building to the Office of the Surgeon General. Renovations included gutting the building and installing three floors — the top floor for the Army Medical Museum and the first and second floors for the Surgeon General's library and the records and pension division. Under the command of its curator, George Otis, the museum was moved to the newly-renovated theatre in six weeks and would remain there for the next 20 years.

Now known as "Old Ford's Theatre," museum staff continued their studies related to the Civil War, which would culminate in 1884 with the six-volume text Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. The new space allowed them to expand collecting efforts, to include areas like anthropology and photomicrography. Curator Otis wrote to Major William Forwood, a surgeon at Fort Riley, Kansas, "We have removed the Museum, as well as the Records Division of the S.G.O. [Surgeon General's Office] to the large fire-proof building on Tenth Street, remodeled by the Quartermasters' from the old Ford's Theatre structure, and have now an abundance of room and are anxious that the Medical Officers at distant posts should send us contributions." The museum was also able to expand exhibit space for visitors.

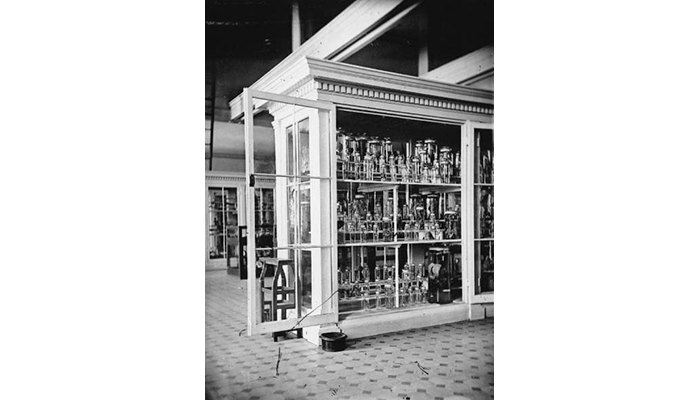

Cabinet with a collection of microscopes in the Army Medical Museum at Ford's Theatre. Circa 1880s. (Woodward 1870)

Despite the museum's research focus, it did not have difficulty attracting the general public. The medical specimens proved fascinating to both professionals and the general public. A certain level of ghoulish curiosity cannot be denied, but overall, a nation still reckoning with the Civil War also came to see the museum as something of a monument to the dead and a place of memorial. This was only enhanced at the Ford's Theatre location, with its ties to Lincoln's assassination. When the museum reopened to the public on April 16, 1867, it posted visiting hours for the first time. The museum drew around 6,000 visitors by the end of 1867 and more each year after.

Perhaps adding to the interest was Dr. S. Weir Mitchell's story, "The Case of George Dedlow," which appeared in July 1866 issue of the Atlantic Monthly. In the story's plot, the fictional Dedlow, who had lost both his legs in the war, was contacted by two spirits during a séance. They proved to be his amputated limbs, preserved in the Army Medical Museum. Mitchell, whose story is notable for its early and evocative description of what would become known as "phantom limb" pain, was no stranger to the museum, appearing several times in museum correspondence.

By 1870, librarian John Shaw Billings had expanded the Surgeon General's Library holdings from 2,000 to 10,000 volumes. The museum and library worked closely together throughout the intervening years but Billings envisioned a wider mission for both organizations.

After Otis' death in 1883, Billings was named curator of the newly-combined Army Medical Museum and Library. The coming decades would bring new scientific breakthroughs that changed and expanded the AMML's purpose and impact. Already, the Civil War research was slowing down and the close of the century would bring a more rigorous focus on bacteriology and infectious disease. As early as 1880, the old Ford's Theatre building was outpaced by its inhabitants and literally falling apart. In 1881 alone, the museum had 40,000 visitors.

In his 1884 speech to Congress, President Rutherford Hayes requested an appropriation to replace the building, stating, "The collection of books, specimens, and records constituting the Army Medical Museum and Library are of national importance... Their destruction would be an irreparable loss not only to the United States but to the world." Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes also advocated for the AMML, saying it "proved to have manifold uses in connection with the general progress of medical science in the United States, especially in relations to the public health, uses which are perhaps of equal importance to the nation." After considerable lobbying by the AMML to local, state, and federal officials, Congress approved a new building on the National Mall, allocating 200,000 dollars to the effort. They selected a site at 7th and Independence Avenue in March 1885. It would become the museum's next home in 1887. Designed by Adolph Cluss, that location came to be known as the Old Red Brick, and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden now resides on its site. But, that is another story.

Resources

OHA 15: Curatorial Records: Letterbooks of the Curators, 1863-1910. Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Henry, Robert S. AFIP, Its First Century. Washington, D.C.: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, 1964.

Lamb, Daniel S. A History of the Army Medical Museum, 1862-1917. Unpublished manuscript. Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Miles, Wyndham Davis A History of the National Library of Medicine: The Nation's Treasury of Medical Knowledge (Bethesda: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1982).

Mitchell, S. Weir (as anonymous), "The Case of George Dedlow," Atlantic Monthly, July 1866.

Olszewski, George J. Restoration of Ford's Theatre, Washington D.C. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service, National Capital Region, 1963.