Warning: The content of this article is only suitable for mature audiences.

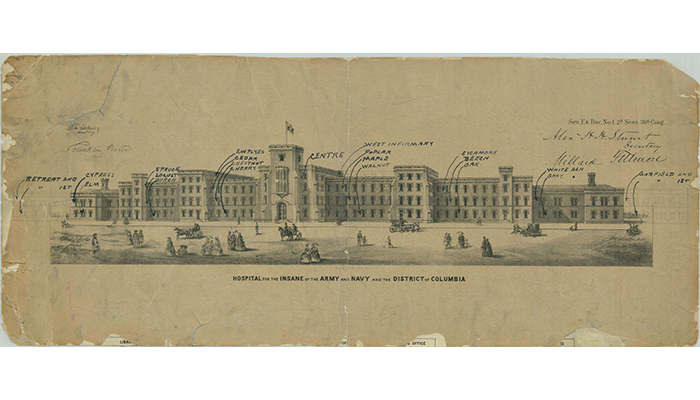

To occupy her mind and her time, Adelaide V. Hall unraveled an old piece of cotton fabric given to her by her nurse and used a needle to turn the thread into an elaborate lace artwork filled with mysterious figures. It was 1917 and 54-year-old Adelaide had been living as a psychiatric patient at the Government Hospital for the Insane in Washington, D.C., known today as St. Elizabeths Hospital, for the previous eight years.

We may have never known of the lace's existence if not for Adelaide's therapist, Dr. Arrah B. Evarts. Evarts practiced a form of therapy known as psychoanalysis, where the doctor uses a patient's thoughts, feelings, dreams, and obsessions to find, interpret, and resolve conflicts. Evarts sat down with Adelaide and asked her to talk about the figures in her lace hoping they would provide insight into her patient. She turned these discussions into a long and detailed article in the October 1918 issue of the Psychoanalytic Review, where we learn about the lace, Adelaide's life, her illness, her obsessions, and how Evarts interpreted her conflicts. The figures are a mixture of inspirations, including real and fictional characters, old lovers, and even herself wedded to her own father. Through them, Adelaide revealed a fixation on marriage, sexual desire, sin, and religion. (A detailed description of each figure can be found here.)

Close-up of Adelaide Hall's lace showing two figures identified as Jack and Jill from the nursey rhyme. The figures could also symbolize Samson from the biblical story and Queen Victoria. (170213-D-MP902-056-J)

The hospital recognized the importance of this lace and placed it on display in the hospital's small museum on psychiatry. In 1995, the U.S. government transferred the hospital to the District of Columbia and dispersed the hospital museum. Some of the items, including this small piece of lace and other examples of patient art, came to the National Museum of Health and Medicine where it joined a large and varied collection related to psychiatry and mental health. This lacework is still in its original frame that was made so the viewer can appreciate both sides.

Art historian John McGregor, who visited NMHM soon after the lace arrived, hailed it as an important example of "outsider art." The term is applied to art made by artists without formal training who are "outside" society and the common artistic conventions. Outsider art can illustrate extreme mental states, fantasy worlds, and unconventional themes, which McGregor discusses in an extensive 1999 article about the lace and its maker in Raw Visions magazine.

Even Evarts said as much, writing about artwork created by her patients and their value to the therapist: "Most of us find our expression along well-recognized and useful lines, because of the demands of society, and also because of the censor of consciousness. That small class of individuals who are unable to accede to the demands of society, and are finally segregated in institutions for the insane, for whom the censor is often tricked or overwhelmed, give expression to the unconscious with a freedom and naivete that is most enlightening."

Most women in Adelaide and Evarts time were trained at a very young age in sewing and needlework to make clothes, maintain their home and earn money. Adelaide, in fact, was a professional dressmaker. Evarts noted that many of her female patients used their skills to create their own works of art:

"They decorate their clothing with embroidery, which is often designed entirely by the patient and worked without a pattern. One woman in St [Elizabeths] Hospital is dressed almost entirely in lace of her own manufacture. One patient covers bits of muslin almost solidly with her embroidery, then wears them as headdresses, shawls or aprons. Another has made a complete dress and had from white muslin covered with brilliant red and blue embroideries of lines and tracing, flowers and even human figures."

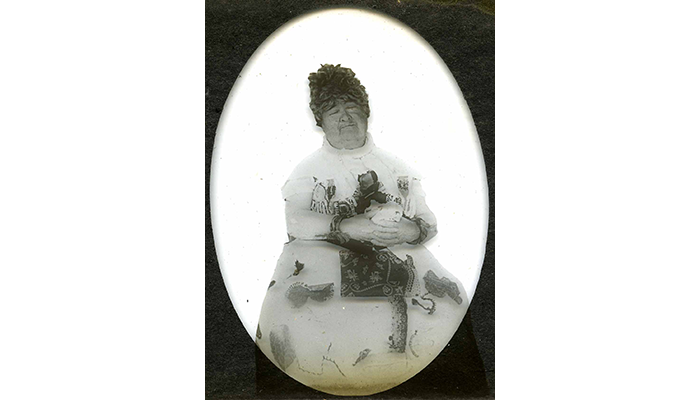

A glass lantern slide photograph in the St Elizabeths collection at NMHM shows an unnamed woman in a dress that appears to be decorated similar to what Evarts describes. (SEH 4-076)

St. Elizabeths arbitrarily discarded patient files in the 1970s, so our only information about her mental state is through Evarts' article. She described a woman who was frequently delusional, formerly addicted to morphine, suffered from syphilis at some point in her life, and who cycled between excitement, aggression, and profound depression.

According to Evarts, Adelaide created her lace in a period of calm, working from one side to the other, sprinkling the designs as she thought of them without a pattern. Not long after, she reverted to a state of deep depression and Evarts had to wait until she emerged to talk about it.

Adelaide tells of a childhood of physical and sexual abuse by her father. She describes her father as mean and cruel when drunk, who beat her often. She would never refer to him as father but as "Mr. Hall" or other names, and said he was the first man she ever slept with. At some point she ended up living in a barn where she shared a bed with him and her brother. These traumatic life experiences heavily influenced the designs in her lace.

Close-up of Adelaide Hall's lace depicting a figure called Mr. Hall or The One Man. Mr. Hall is the name commonly given to Adelaide's father. (170213-D-MP902-056-UN3)

Evarts used the pseudonym "Virginia" for Adelaide in her article to protect her privacy. However, she provided enough biographical information that, through some sleuthing by John MacGregor in preparation for his own article, revealed her real name. Author Michael Little took the research further and traced her life through historic records, often confirming the general truth of many of Adelaide's memories. Adelaide was the 8th of 9 children born sometime between 1862 and 1863 in Guilford, Virginia to James and Adeline Hall. After her mother died in 1869, she and a brother lived with her father in Virginia until she was removed by an older sister at the age of 13 to live in Washington, D.C. Adelaide was never married or had any children, although she mentioned several lovers and reported at one point that she had been a prostitute (although family members said the latter was not true). She appeared to have been successful as a dressmaker during her early adulthood and lived comfortably for a time.

In the end, however, Evarts was disinclined to believe that Adelaide had actually suffered from abuse and that these obsessions were only about her desires and conflicts with sexuality. Psychoanalysis and therapist's interpretations of a patient's dreams and thoughts can be highly subjective. They may be limited to the doctors own life experiences or prevailing cultural ideas of the era. Evarts was a product of her time. She dismissed Adelaide's description of a beating by her father, stating, "They were probably but the efforts of a misguided man trying to bring up his motherless baby girl." Later she wrote of another beating one night, stating "the more likely thing, again to return to probabilities, is that this is the only way her father could care for her at night when she was a baby and a tiny girl."

What benefit Adelaide received from the psychoanalysis or any further treatment for her trauma and disorder are unknown. She never left the hospital and would remain there until her death in 1945 at the age of 82.

Resources

Evarts, Arrah B. "A Lace Creation Revealing an Incest Fantasy." The Psychoanalytic Review Vol V, No 4 (Oct 1918): 364-380.

MacGregor, John. "The Lacemaker." Raw Visions No. 26 (Spring 1999): 24-30.

Little, Michael. "Lunatic Fringe: Stitching Together the Life of DCs visionary Lace Maker." The Washington City Paper, May 21, 2004.

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.