With nearly 25 million objects, we're only able to display a small percentage of the museum's collections at a given time. Loans and collaborations with other institutions are an important way we extend the museum's value beyond our physical walls. Loans allow the museum to increase public exposure to the collections and foster a deeper appreciation for the history and advancement of military medicine.

Recent collaborations with Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) and James Madison University included loaning artifacts for exhibits.

An exhibit of artifacts and materials from the museum's Historical Collections and Otis Historical Archives were displayed during a Nov. 14, 2018, special event at the Gorgas Library, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Maryland. (181114-D-MP902-0009: Department of Defense photo by Matthew Breitbart)

On Nov. 14, 2018, we loaned objects from collections to WRAIR for their 125th anniversary. The exhibition, titled "Center for Military Psychiatry and Neuroscience: Walter Reed Army Institute of Research," included artifacts from our Historical Collections and Otis Historical Archives. The display was part of the celebration of WRAIR's 125 years of military biomedical research. Exhibits included photographs documenting military psychiatry, an Infrascanner Model 200 and Eye-Sync System used for traumatic brain injury diagnosis, and much more, exemplifying innovations in military research and technology.

Opening day of "Colonial Wounds/Postcolonial Repair," an exhibit on display from March 12 to April 13, 2019, at James Madison University. (Image courtesy of JMU photographer Elise Trissel.)

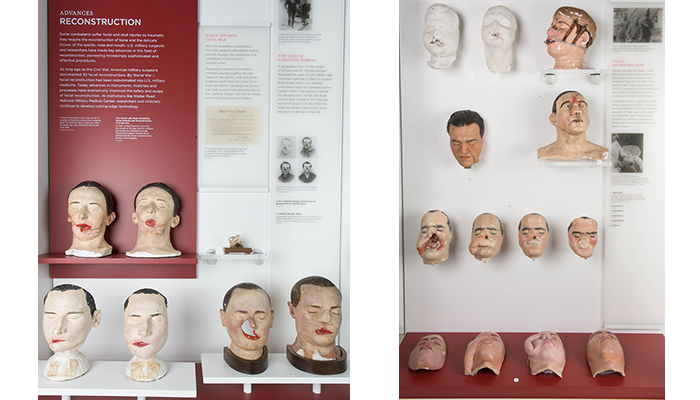

In spring 2019, we loaned materials to James Madison University for an exhibition titled "Colonial Wounds/Postcolonial Repair." The exhibit focused on the history of French colonialism and colonial violence through the lens of contemporary Algerian artist Amina Menia. The museum's contributions of medical illustrations, photography, facial molds, film, and artifacts from World War I allowed for a deeper contextualization of the trauma of Algerian soldiers under French colonial rule.

Dr. Maureen Shanahan, co-curator for the exhibit, said, "What the [NMHM] collection offered to me, and the collection offered many things, was a way to show the dramatic wounds that World War I produced. It offered multiple media–the pastels, the photographs, the Red Cross film, and the objects–that conveyed the wounds in different ways."

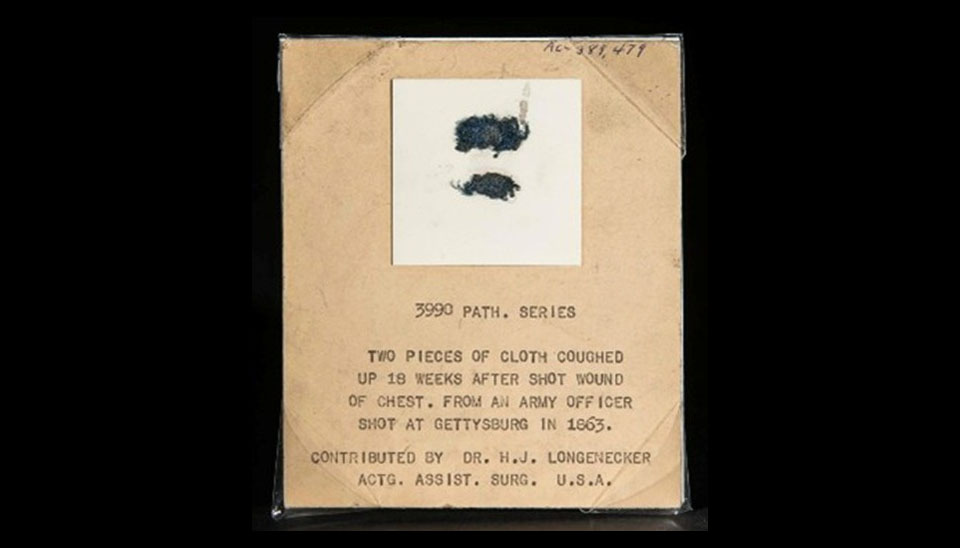

WWI was the first large-scale war fought with mechanized weaponry. The military was introduced to new types of industrial warfare involving land mines, tanks, poison gas, and high-powered rifles. These methods of combat presented unique injuries and impetus to treat these injuries.

Facial molds from the museum's Historical Collections exhibited in "Colonial Wounds/Postcolonial Repair" are on display from March 12 to April 13, 2019, at James Madison University. (Image courtesy of JMU photographer, Elise Trissel.)

"Especially impactful [in the exhibit] were the plaster molds and pastels and photographs dealing with facial wounds," said Shanahan. As Murray Meikle mentions in his book "Reconstructing Faces: The Art and Wartime Surgery of Gillies, Pickerill, McIndoe & Mowlem," trench warfare greatly increased the occurrences of head and face injuries because the head was exposed; an estimated 15 percent of all soldiers sustained head and face injuries. A new kind of treatment was required to resolve these types of injuries.

Skin graft surgeries, like the tubed pedicle graft devised by Harold Gillies, allowed for a flap of skin from a different part of the body to be placed on the affected area. The donated skin would gradually spread out, replacing the scar tissue from the wound and restoring the damaged area.

Objects showing facial reconstruction on display in the museum's Innovations in Military Medicine exhibit gallery. (Left: 150721-A-MP902-012, Right: 150722-A-MP902-023: Department of Defense photo by Matthew Breitbart)

Prior to the opening of "Colonial Wounds/Postcolonial Repair," Shanahan and her students visited the museum to further enhance their knowledge of World War I injuries, including facial wounds. The museum's exhibit about advances in reconstruction (see image above) details the progress of facial reconstructive surgery in military medicine through plaster models of skin graft surgeries. At institutions like Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, researchers and clinicians continue to develop cutting-edge technology to manage facial injuries.

"Colonial Wounds/Postcolonial Repair" was a well-visited exhibition allowing a wide audience to explore more of our collections. We continue to welcome collaborations through loans to increase visibility of the vast collections on hand.

Resources

Meikle, Murray C. Reconstructing Face: The Art and Wartime Surgery of Gillies, Pickerill, McIndoe & Mowlem. Otago University Press, 2013.

Relevant Links:

The Tubed Pedicle Flap in Reconstruction Surgery

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1657906/

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.