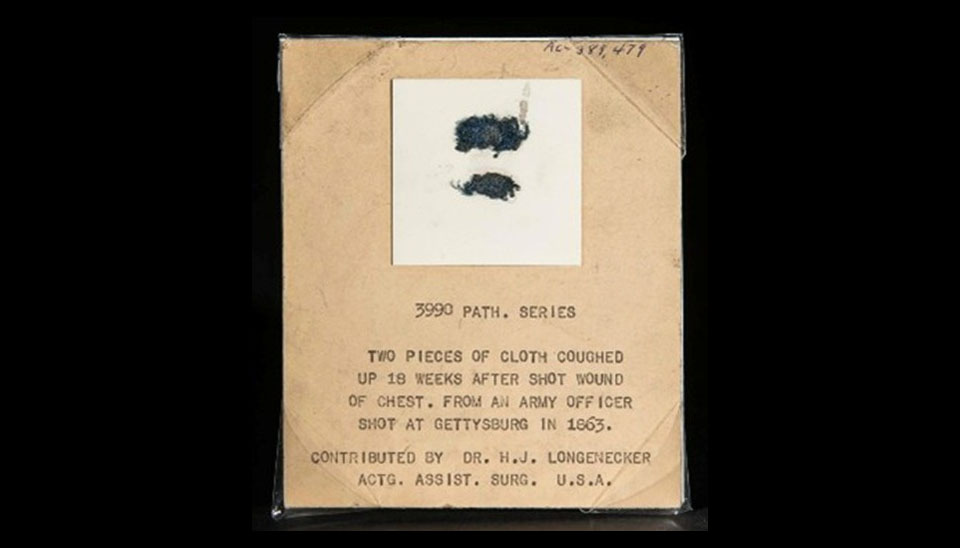

As the U.S. recovered from the Civil War, its military turned its attention beyond maintaining a martial force to pursuits that frequently expanded our understanding of science. The post-war efforts of the Army Medical Museum (now called the National Museum of Health and Medicine), included compiling the definitive medical and surgical history of Civil War, creating a comprehensive collection of medical specimens, and refining the study of optics and microscopy.

The last pursuit is what brought the Army Medical Museum to the attention of Commodore B.F. Sands, Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Observatory. While planning an expedition to study the total eclipse of the sun (when the moon blocks the sun from the earth), Sands asked the Surgeon General of the Army for assistance from the Army Medical Museum. Much of the request was owed to the incredible expertise museum personnel had in scientific photography.

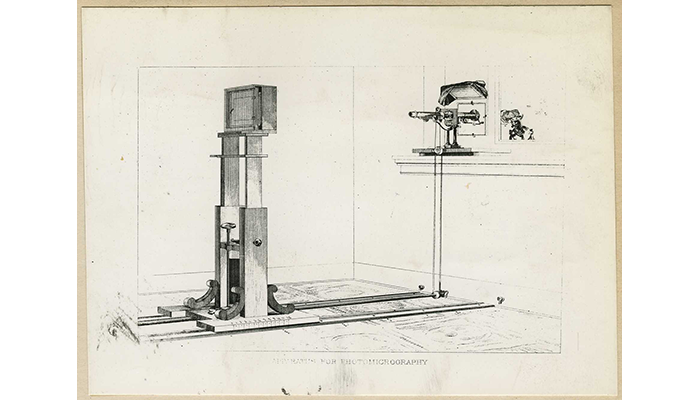

Illustration of the photomicrograph apparatus, created by J.J. Woodward and Edward Curtis, that shows the use of natural light focused through a microscope and deposited onto a glass plate negative held in a wooden frame. (Reeve 72508)

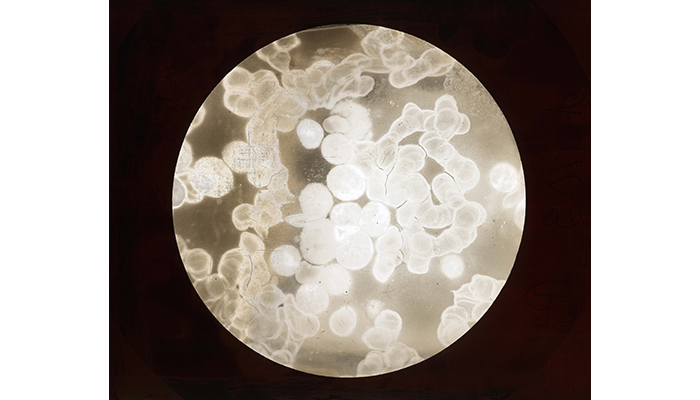

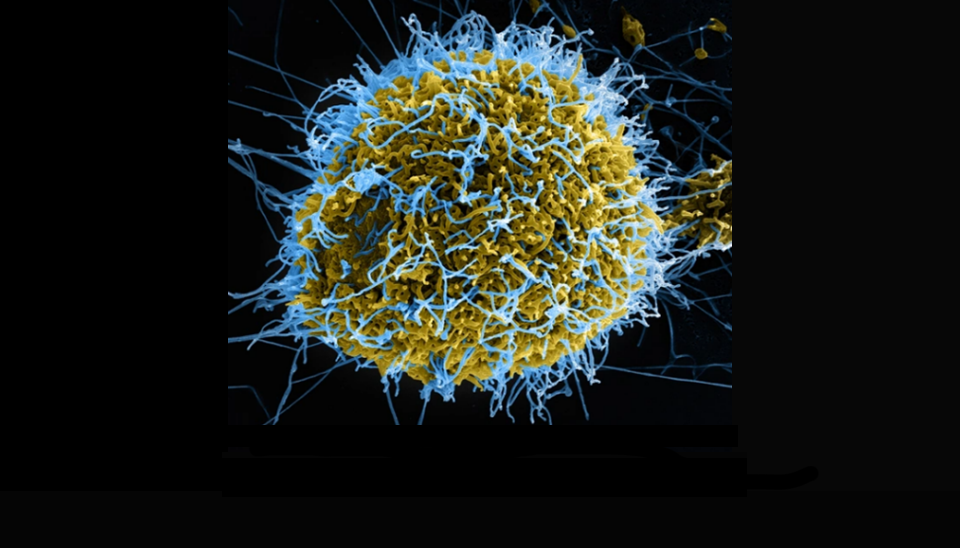

Photomicrograph of an organ's blood affected by leukemia, showing an increase of white blood cells, amplified x1000. (WW 1944).

Photomicrographic apparatus, heliostat, Army Medical Museum. A heliostat is a device used to reflect and direct the sun's light. The heliostat turns to keep reflecting sunlight toward a predetermined target, compensating for the Sun's apparent motions in the sky. This allowed slow exposure of photomicrographs producing a clearer image. (WW 1580).

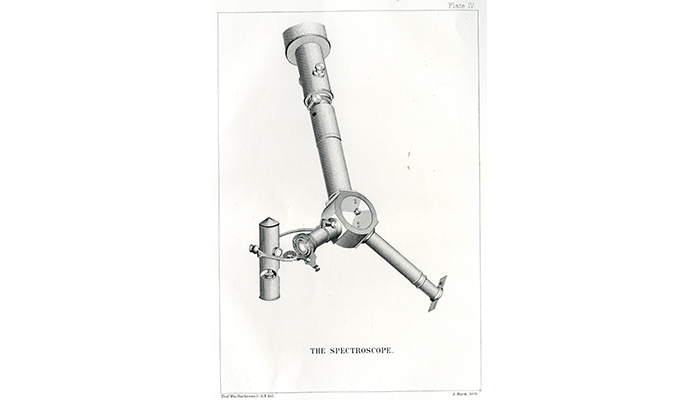

Curtis, who led the team, was assistant to Dr. Joseph Janvier Woodward at the Army Medical Museum. Woodward was the curator of the Microscopical Collection. He helped pioneer the creation, and refinement, of photomicrography, the process of taking photographs through a microscope. He and Curtis improved upon existing techniques to produce clearer images of microscopic subjects. The clearer, more detailed images allowed early microbiologists to see previously unobservable microscopic details in samples. Curtis was, therefore, tasked with adopting the techniques of photomicrography to stellar photography. With the principal being roughly the same, Curtis and his team modified a telescope by attaching a camera box to the eye tube.

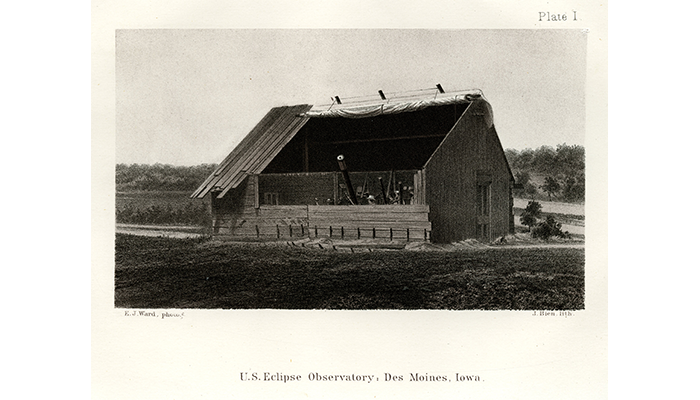

Plate I. Exterior of the U.S. eclipse observatory, Des Moines, Iowa, Aug. 7, 1869. (OHA332-001-00001-1)

In their early experiments in photomicrography, Curtis and Woodward used a heliostat, an apparatus that reflect sunlight to through the glass of a microscope slide and onto a chemically treated glass negative plate that would react to the light to produce an image. The heliostat adjusted to the sun's changing position in the sky keeping light exposure consistent unlike a static reflective surface. The telescope, in this case, would act as both the heliostat and the microscope. The light of the sun would shine directly through the telescope's reflectors and onto a chemically treated glass negative plate in the camera box. The photosensitive chemicals would react to the light to produce an image.

A spectroscope was used to determine the chemical composition of the sun's corona during total eclipse. (OHA332-001-00001-4)

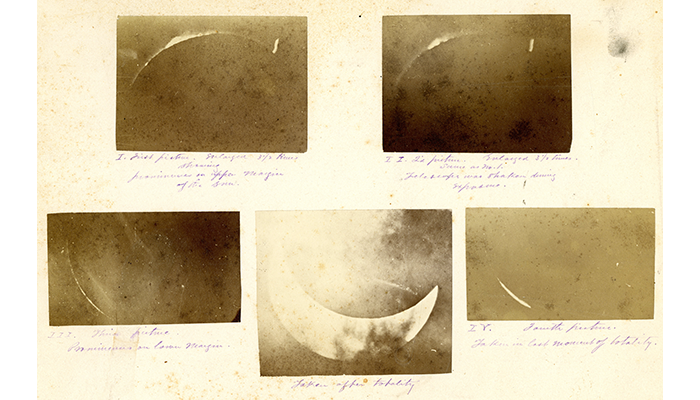

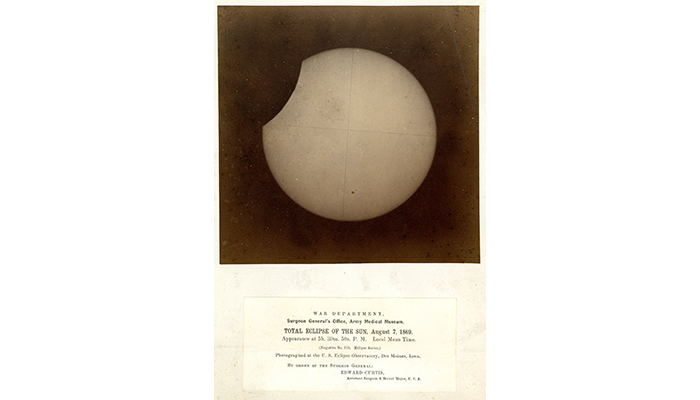

The team made the trek to Des Moines, Iowa, in late July to set up and calibrate their equipment before Aug. 7, 1869, when the solar eclipse would occur. Sadly, when the day arrived, there was a haze that, through the moisture in the air, would distort the image of the sun. However, the team would not be dissuaded. After a few calibrations, widening the lens' aperture, and trying varying lengths of exposure, they photographed the sun throughout all phases of the eclipse.

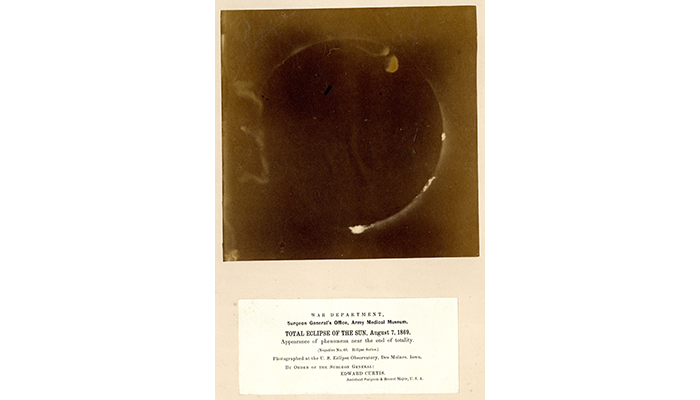

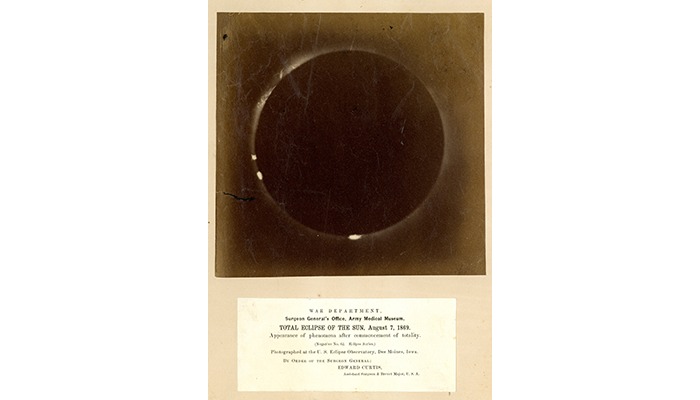

Appearance of phenomena after commencement of totality, Total Eclipse of the Sun, Aug. 7, 1869, photographed at the U.S. Eclipse Observatory, Des Moines, Iowa. (OHA332-001-00005)

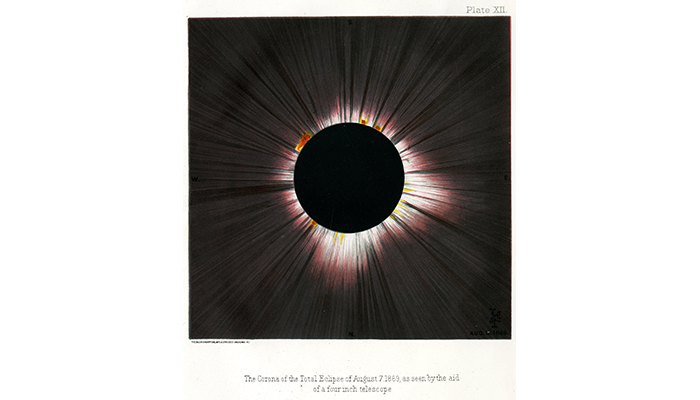

To contend with the haze, the exposure time of each negative had to be prolonged, which resulted in fewer photographs taken than expected. The resulting photographs, however, were among the clearest images of a solar eclipse recorded at that time. The two negatives exposed during totality recorded an incredible level of detail. Major topographic aspects of the moon were highlighted by the corona, or halo effect, that occurred around the silhouette of the moon during total occlusion of the sun. This phenomenon can be witnessed only from an area of Earth directly aligned with the sun and moon during an eclipse.

With the help of Woodward and Curtis' lenses and their experience in scientific photography, on Aug. 7, 1869, at 3:00 p.m., astronomers were able to capture incredible, new images of a total solar eclipse. Innovations originally designed to capture the smallest medical images were, instead, used to help photograph the largest object in our solar system, which would help us better understand our solar system.

Resources

OHA 332 Total Eclipse of the Sun Collection, 1869.

Sands, Commodore B.F, U.S. Navy, Superintendent of the U.S. Naval Observatory, Washington, D.C.; "Reports on Observations of the Total Eclipse of the Sun, August 7, 1869," (Washington: Government Printing Office); 1869.

"Photographs of the Total Eclipse of the Sun, August 7, 1869," (Washington: Surgeon General's Office, Army Medical Museum); October 9, 1869.

Relevant Links:

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.