"Since museums are public collections, it's important for them to connect with the public on other ways of thinking and looking at what a collection is," said Beverly Ress, a professional artist who has been working with the National Museum of Health and Medicine for nearly seven years.

While the museum's collections are visited frequently by scientific and medical researchers, another variety of visitors are professionals artists, like Ress, who draw inspiration from the collections to produce art. On the other end of this working relationship, the artists broaden understanding of the museum collections by bringing a different perspective to the objects and specimens.

Beverly Ress, a professional artist, draws a kidney specimen from the museum collection. (190819-D-YQ624-1002): NMHM photo)

Elizabeth Lockett, the museum's Human Developmental Anatomy Center collections manager, a trained medical illustrator herself, is often the point of contact for artists wanting to access the collection. "Most artists have a general idea of what they want to see when they come in, but we also guide them towards specimens and artifacts of potential interest," said Lockett.

With a collection of nearly 25 million objects, there are a large number of items artists can work with. Many artists and illustrators use the collections as models or references for drawing human anatomy. However, some artists, like Ress, see an intrinsic quality to the specimen that drives their interest.

Beverly Ress, a professional artist, draws a kidney specimen from the museum collection. (190819-D-YQ624-1004): NMHM photo)

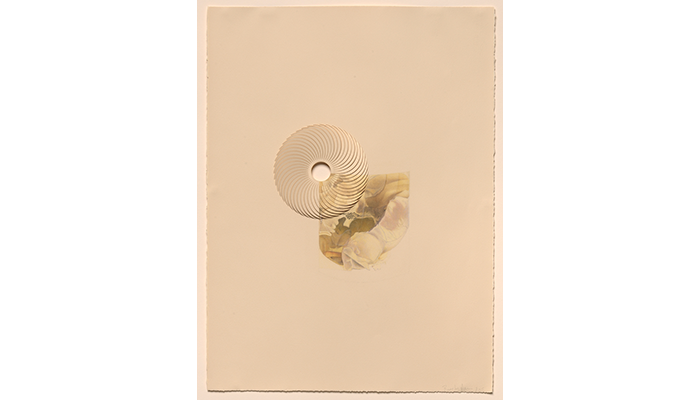

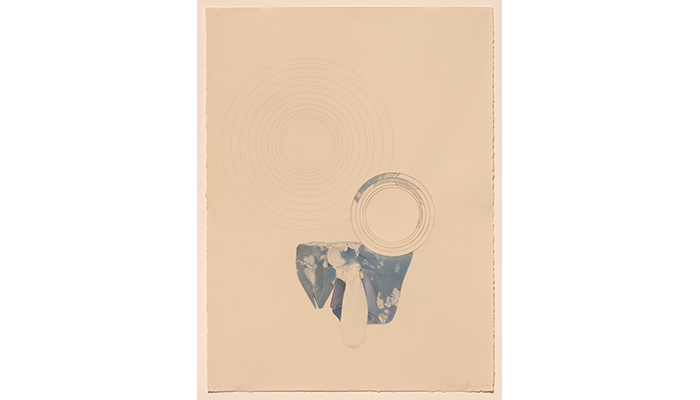

Ress, a multi-media artist, views the collections as documenting a specific period of modern society. Ress came to the museum searching for items that record this idea of philosophical mortality: a chronicle of human existence.

After capturing the specimen in a representational drawing, Ress then manipulates the drawing in a distinct way. Cutting into it, folding a part of it, or laying watercolors on top of it, the drawn specimen becomes art that plays on the interrelations between science, art, and death. "My art asks us what dying can teach us about living," said Ress. The museum's collections inspire her as symbols of a human presence that live on after death.

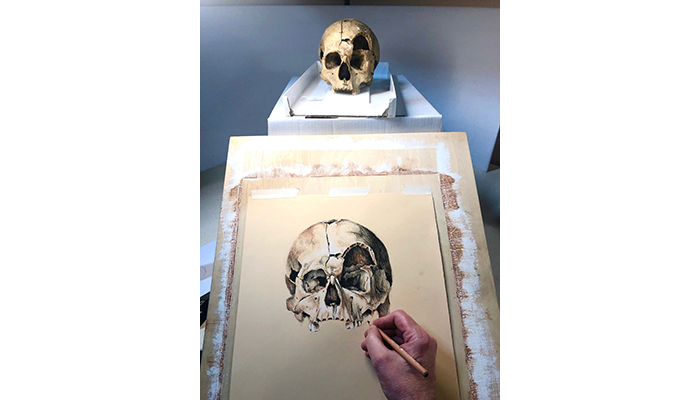

Paul Glenshaw, a professional artist, sketches a Civil War skull from the museum's Anatomical Collections. (190820-D-YQ624-1001: NMHM photo)

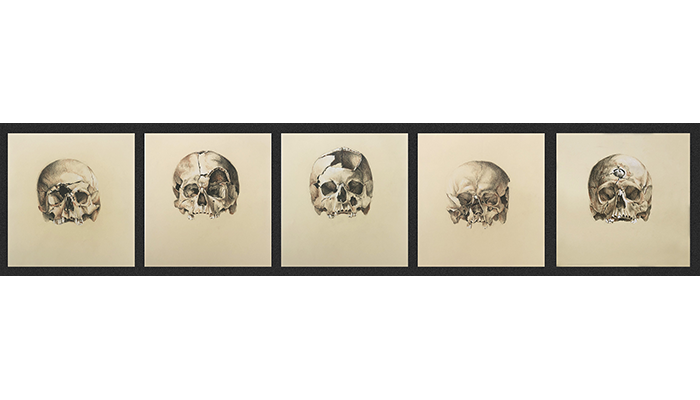

Another artist, Paul Glenshaw, is currently working with Anatomical Collections Manager Kristen Pearlstein to draw a series of Civil War skulls.

The skulls, primarily from the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864, were collected to record the history of military medicine. According to Pearlstein, the skulls exhibit evidence of trauma from projectiles and the subsequent fracturing. Studying the skulls yielded an early understanding of radiating fractures, directionality of breaks, and how skulls fracture under external forces.

The trauma was then recorded among other facial and head wounds in the "The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion." This six-volume publication, prepared by Surgeon General Joseph K. Barnes and staff members from the Army Medical Museum (our predecessor), was an important source of information for contemporary physicians.

A series of five Civil War skull sketches drawn from specimens in the museum's Anatomical Collections by professional artist Paul Glenshaw. (190821-D-D0458-1002: photo by Paul Glenshaw)

Through his sketches, Glenshaw wants to remind us of the human rather than physical importance of the skulls. "When you see the human skulls all lined up, all seen from the front, on the exact same size of paper, and drawn with the same equipment, what pops out is all the differences, and how unique each one of them was as a human being," said Glenshaw. Glenshaw sees the stories behind the skeletons and declares he is making a portraits of these Civil War soldiers rather than producing an anatomical reference.

Paul Glenshaw, a professional artist, sketches a Civil War skull from the museum's Anatomical Collections. (190821-D-D0458-1001: photo by Paul Glenshaw)

While we provide a place for artists to be inspired by artifacts and specimens related to the history and research of military medicine, in certain cases, artists, like Ress and Glenshaw, provide a new perspective for considering the artifacts in question. "They [the artists] have a different point of view that is crucial for the public to see. These specimens have value beyond just research, they are intrinsically interesting and lovely objects," said Lockett.

A museum visitor emphasizes the dark coloration of a plastinated heart as she finishes her watercolor illustration during the conclusion of the Feb. 9, 2019, Techniques of Medical Illustration: Watercolor program at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland. (190209-D-MP902-0043: NMHM photo)

Through formal research requests, we are able to welcome and support artists who desire to use our collections as models, references, or inspiration for their work. Similarly, our free and public Techniques of Medical Illustration program, led by Lockett, allows visitors to try their hand at making illustrations of specimens and artifacts from the museum's collections.

Those interested in using the collections for research can contact us at (301) 319-3300 or by email at USArmy.Detrick.MEDCOM-USAMRMC.List.Medical-Museum@mail.mil.

Resources

Explore the collections for artistic inspiration:

U.S. Surgeon General's Office. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Government Printing Office, 1883. https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-14121350R-mvset

Relevant Links:

Watercolor Medical Illustrations Make a Splash at the Medical Museum

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.