Private Julius Fabry, Battery K, 4th U.S. Artillery, was seriously wounded at the Second Battle of Deep Bottom, Virginia, on August 16, 1864. A large piece of shrapnel shattered his left leg, and he was treated in the field with an amputation below the knee. Days later, Fabry was sent to Satterlee Hospital, Philadelphia, where additional operations took place to treat his injury. These culminated in another amputation, this time above the knee, at the lower third of the thigh.

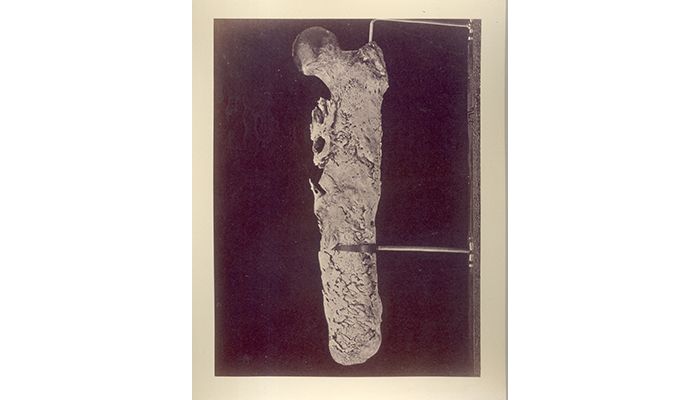

The partial left femur of Private Julius Fabry, Battery K, 4th U.S. Artillery, successfully reamputated at the hip for chronic osteomyelitis of the femur. (SP 274)

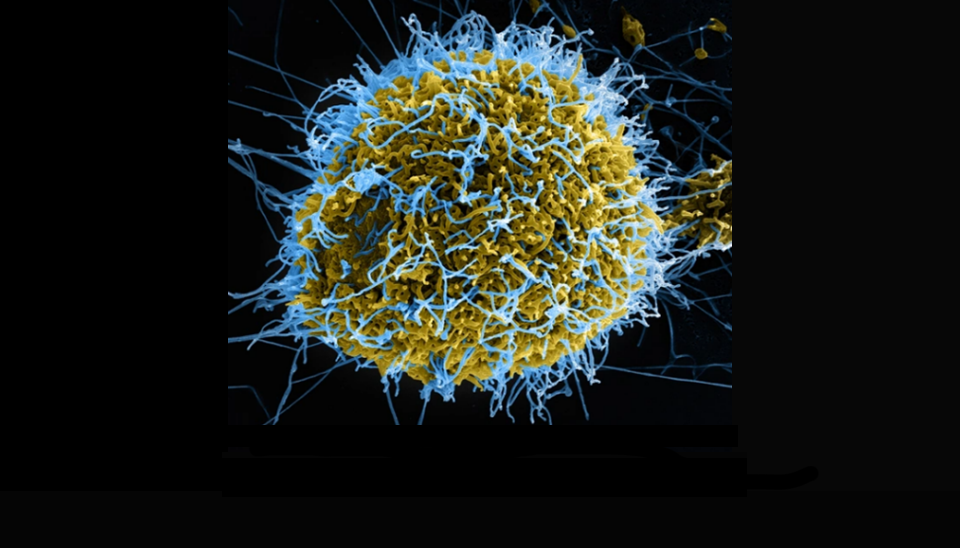

Like many Civil War amputations, Fabry's wound was likely contaminated by unsterilized surgical instruments and developed into osteomyelitis, a bacterial infection of the bone. Advanced cases of osteomyelitis are characterized by areas of dead bone tissue where the blood supply has been disrupted (necrosis), surrounded by areas of reactive bone formation where the bone has attempted to repair itself in response to inflammation and infection. Fabry's injury developed into an advanced case of osteomyelitis, and for several years Fabry suffered from the recurrence of abscesses of the thigh and detachments of necrotic pieces of bone. Additionally, complications in the tissue repair of the femur resulted in formations of bone extending into the surrounding muscle and soft tissues, a process called heterotopic ossification.

In October 1867, Assistant Surgeon John Shaw Billings, who would later become a curator at the Army Medical Museum (AMM, now NMHM), performed an exploratory operation on Fabry and removed a button-sized piece of bone with a small cylindrical blade saw known as a trephine. The operation revealed the entire femur was comprised of dead bone surrounded by layers of irregular new bone. The suggested course of action was to separate the femur from the hip and remove the entire diseased bone.

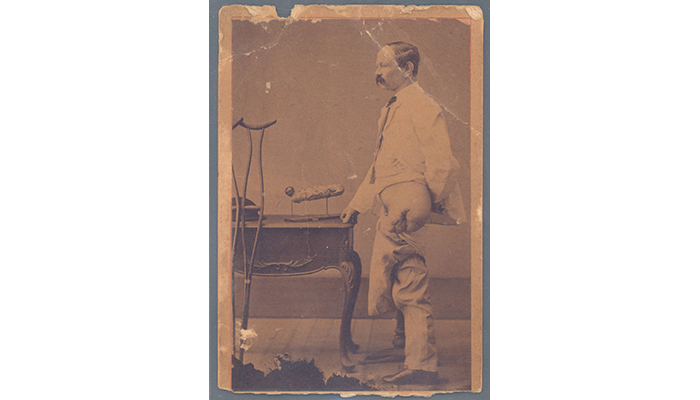

Private Julius Fabry, Battery K, 4th U.S. Artillery, shows his amputated leg after its successful reamputation by George Otis. (SP 274)

Fabry resisted surgery until May 15, 1870. On this day, AMM Curator and Assistant Surgeon George A. Otis, assisted by other AMM staff including Assistant Surgeons Joseph J. Woodward and John S. Billings, performed a disarticulation and tertiary amputation, completely removing the femur from the hip. Within three weeks, Fabry was up and moving with crutches for support.

However, in July 1892, Fabry fell and struck the left side of his back, damaging his kidney. At the time he was admitted to the hospital, he was in the habit of using morphia (morphine) to manage his chronic pain and was recorded as "anxious to give it up." Addiction was not yet well-defined or understood, and opium or morphine dependence was viewed as a behavioral problem, rather than a physical disease.

Fabry was readmitted to the hospital in December 1893 "for the opium habit." On January 9, 1894, Fabry "secured some morphia and unintentionally took an overdose," from which he died on January 10, 1894.

Left thigh bone of Private Fabry removed after 6 years of infection (AFIP 1000313) next to a photograph and book describing his case. Fabry was photographed in the early 1870s to show the results of his operation (SP 276).

Today, the remodeled pelvis and amputated femur of Private Fabry are on display at NMHM. Fabry serves as a reminder of the chronic pain and unresolved infection many soldiers experienced in the decades following the Civil War and continue to experience in the current combat environment. Osteomyelitis and heterotopic ossification remain common complications in combat-related injuries and amputations. Fabry's reliance on opiates to manage his pain, and subsequent overdose, also remind us how treatment challenges for chronic pain continue to face our military and civilian medical communities.

Resources

AFIP 384637, OHA 31, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine

Relevant Links:

War Surgery in Afghanistan and Iraq: A Series of Cases, 2003–2007, edited by Shawn C. Nessen, Dave E. Lounsbury, and Stephen P. Hertz. Falls Church, VA: Office of the Surgeon General, United States Army; Washington, DC: Borden Institute: Walter Reed Army Medical Center; 2008.

Eisenstein, N., Stapley, S. and Grover, L. (2018), Post–Traumatic Heterotopic Ossification: An Old Problem in Need of New Solutions. J. Orthop. Res., 36: 1061-1068.

Tribble DR, Lewandowski LR, Potter BK, et al. Osteomyelitis Risk Factors Related to Combat Trauma Open Tibia Fractures: A Case-Control Analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(9):e344-e353.

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.