The term "asymptomatic" has been prevalent in every internet search engine since the COVID-19 health crisis began dominating the lives of people all over the globe. Many people have quickly learned what it means to be an asymptomatic carrier, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as "passive or healthy carriers…who never experience symptoms despite being infected." "Human carriers," as they were once called, were conceived of by scientists as early as the 1870s. One such person was the infamous "Typhoid Mary."

Not just a turn-of-phrase, Typhoid Mary was a real woman named Mary Mallon. She emigrated from Ireland to New York in about 1883, and in summer 1906, was a temporary cook in the home of a wealthy banker. By that September, within a month of beginning work, typhoid fever had spread to six of the 11 people in the household. The family hired sanitary engineer George Sober to determine how the illness had spread through the family. Today, we would call him a contact tracer, a person who traces the movements of a person infected with a pathogen, like typhoid, and identifies who they have been in contact with in order to prevent further spread of the illness.

After studying potential sources like contaminated water, Sober determined contact with Mallon was the cause of the outbreak, and in 1907, she became the first person in North America identified and analyzed as a "healthy carrier" of typhoid. Sober had traced her history of contact, primarily through employment agencies, and found typhoid cases wherever she worked. To use a term with which we are increasingly familiar, Sober realized Mallon was an asymptomatic carrier of the bacteria Salmonella typhi.

It is at this point that the legend of Mary Mallon truly begins. She has been studied by all manner of disciplines – from historians and medical ethicists to scientists and public health officials. By understanding Mallon, asking questions of 'right or wrong' may lead us to quick answers, but asking 'how' and 'why' has led scholars to more complex ones.

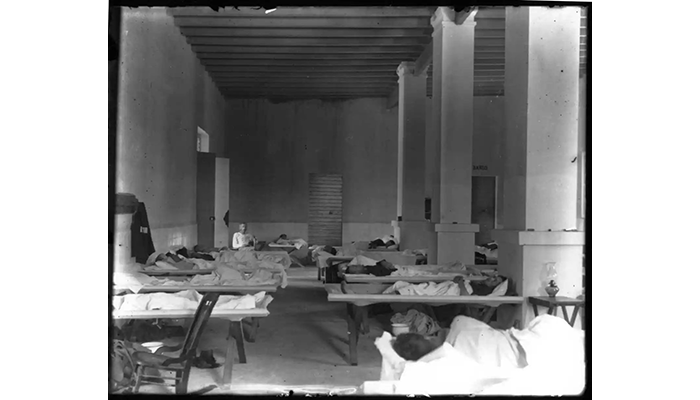

Ward with typhoid cases at military hospital in Ponce, Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War. (AMM 154)

Upon finding Mallon, Sober attempted to obtain samples of Mallon's blood, feces, and urine, explaining that she carried typhoid fever. However, Mallon could not believe she, being perfectly healthy, was infecting people, and chased Sober away. At about this time, 3,000 New Yorkers had been infected with typhoid, and Mallon, who had worked in eight different homes, was probably a significant factor in the outbreak.

Sober began following Mallon around New York, trying to collect excreta from her, while she became more agitated. Sober describes his pursuit almost as a cat-and-mouse game, but for her, it must have been terrifying. Mallon was literate but it is unlikely she understood the finer points of Sober's scientific explanations, if he offered them, as he appeared even in the homes of her friends.

Eventually, Sober went before the New York Department of Health, arguing that Mallon needed to be tested, for the safety of the public. She was taken by force to Willard Parker Hospital where laboratory tests proved she had high concentrations of typhoid bacilli in her excreta. Mallon was quarantined at Riverside Hospital on North Brother Island near New York City, and in 1909, after two years there, she unsuccessfully sued for release. The next year, the new health commissioner decided to free Mallon, as long as she would not work as a cook. In return, the city would help her find employment as a domestic worker.

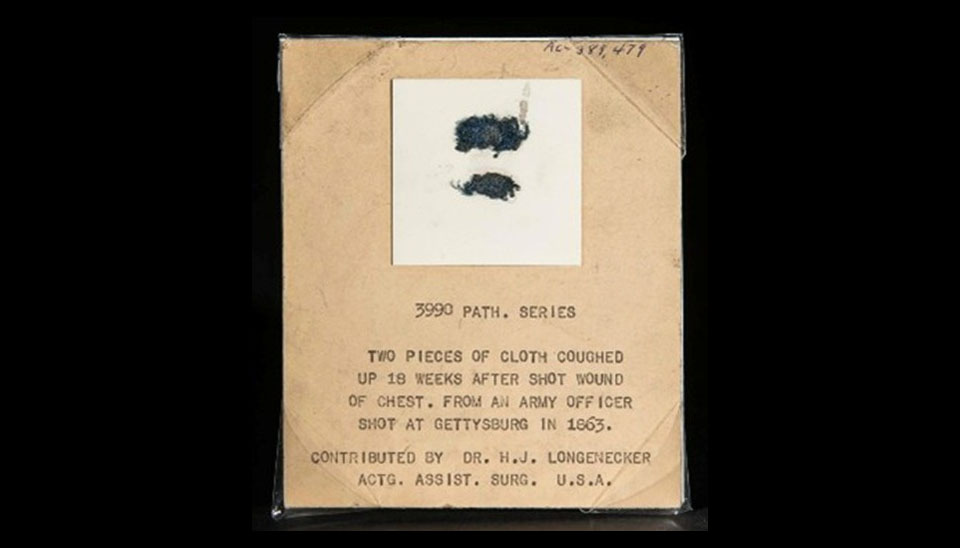

Intestinal specimen from a soldier afflicted with typhoid, 1861. The fever caused intestinal perforation and was fatal to the patient. (PS7819)

Mallon was released, but ultimately did not abide by these terms. It may be she still did not believe that she was a health risk, or perhaps domestic service, which paid significantly less, was a role Mallon could or would not sustain.

Mallon was arrested in 1915 after she was found working as a cook under the name Mary Brown at Sloane Maternity in Manhattan. In her three months there, at least 25 people were diagnosed with typhoid and two had died. She was returned to North Brother Island and would spend the rest of her life, 26 more years, in isolation there.

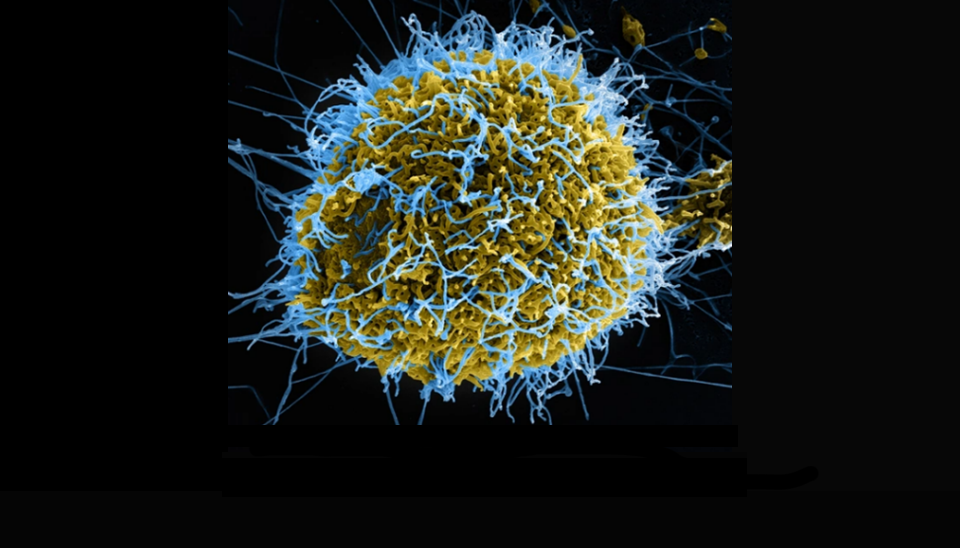

When Mary Mallon died in 1938, the New York City health authorities had identified more than 400 known asymptomatic carriers of Salmonella typhi but none had been quarantined. In the intervening years, sanitation improved, there was more access to clean drinking water, and a new vaccine had been developed at the Army Medical Museum (now the National Museum of Health and Medicine) and School (now the Walter Reed Army Institute of Medicine).

Mallon was caught up in a system that treated her more as a threat than a patient. Health authorities believed they had no other choice than to quarantine Mallon, as she refused any precautions to ensure public safety. The outbreaks of disease in cities like New York were absolutely devastating. To simplify her story is to do it a disservice, as it raises innumerable questions about medical ethics and is considered by most experts to be a turning point in our understanding the intersecting questions surrounding public good, personal freedoms, scientific discovery, and patient rights, to name but a few.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. "Principles of Epidemiology in Public Health Practice: Chain of Infection." Last modified May 18, 2012.

Chan, Kit Yee and Daniel D. Reidpath. "'Typhoid Mary' and 'HIV Jane:' Responsibility, Agency and Disease Prevention," Reproductive Health Matters, Vol. 11, No. 22, (Nov., 2003), pp. 40-50

Leavitt, Judith Walzer. "'Typhoid Mary' Strikes Back Bacteriological Theory and Practice in Early Twentieth-Century Public Health," Isis, Vol. 83, No. 4 (Dec., 1992), pp. 608-629

Marineli, Filio, Gregory Tsoucalas, Marianna Karamanou, and George Androutsos. "Mary Mallon (1869-1938) and the History of Typhoid Fever." Annals of Gastroenterology, Vol. 26, No. 2 (2013), pp 132–134.

Soper, George A. "The Curious Career of Typhoid Mary," Bulletin of the New York Academy Medicine, Vol. 15, No. 10 (Oct. 1939), pp 698-712.

Wald, Priscilla. "Cultures and Carriers: 'Typhoid Mary' and the Science of Social Control," Social Text 52/53, Vol. 15, Nos. 3 and 4, Fall/Winter 1997.

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.