On the evening of July 2, 1863, while commanding the Third Army Corps on the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles rode out to a grassy knoll for a better view of his position and was promptly struck in the right leg by a solid 12-pound shot from Confederate forces. Still upright and astride his startled horse, Sickles lifted his injured leg over the saddle and dismounted unassisted as aid rushed to his side.

Sickles was removed to a sheltered ravine in the rear of his position and Surgeon Thomas Sim, Medical Director of the Third Army Corps, was summoned to assess the injury. A report in the Daily National Republican newspaper indicated, “At first examination [Sim] thought the leg could be amputated below the knee, but after chloroform had been administered, a more critical examination disclosed the fact that the bone was shattered to the knee joint, and it was found necessary to cut above the knee” (Daily National Republican, July 6, 1863). Sim performed the amputation in the field. Sickles was transferred to a Washington, D.C. hospital the next day, accompanied by Sim, where he recovered well enough to be back on a horse two months later.

Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles. Photographed at the Army Medical Museum in 1865. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Otis Historical Archives, Woodward 1760.

A year prior to Sickles’ injury, Surgeon General William Hammond ordered the establishment of the Army Medical Museum (AMM) and directed medical officers to collect and forward all specimens, artifacts, and medical reports pertaining to battlefield trauma and treatment for the study of military medicine. Surgeon John H. Brinton, first director of the AMM, detailed his role at Gettysburg.

“My duty at this time was twofold, first to render what help I could surgically, and secondly, to collect specimens and histories for the Museum. I was able to gather much for the Museum, and for the most part the medical officers were anxious to further me in my endeavors to carry out my Washington instructions” (Brinton 1914: 246). Brinton made continuous efforts to educate medical officers about the scientific significance of the growing AMM collection and to impress upon them the value of contributing truthful, detailed case histories. Data from these medical reports and summaries were eventually aggregated into the groundbreaking six-volume Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, the last volume of which was published in 1883.

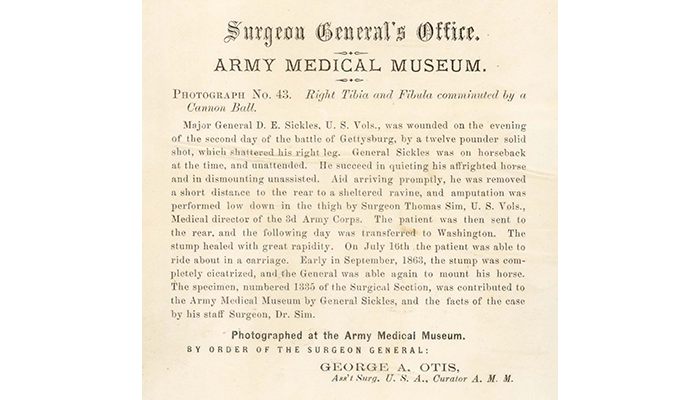

Surgeon General’s Office record for Maj. Gen. Sickles’ right tibia and fibula comminuted by cannonball. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Otis Historical Archives, SP 43.

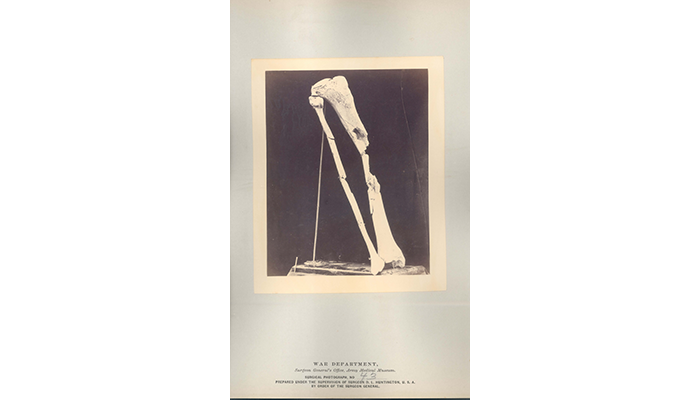

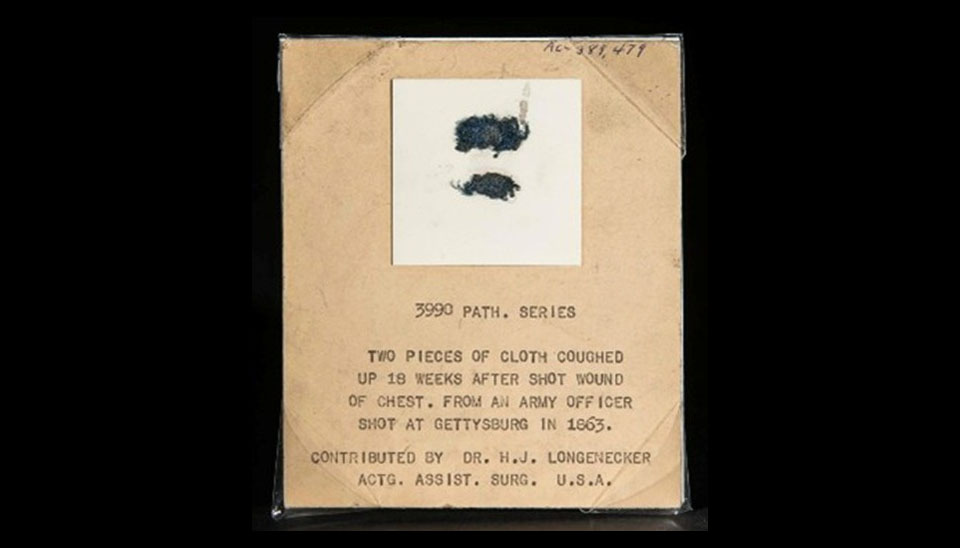

As word of the museum spread, occasionally a medical specimen arrived that was directly contributed by the patient rather than the operating surgeon. Shortly after Sickles’ surgery, he “forwarded [his amputated leg] to the Museum in an extemporized coffin on which was tacked a visiting card ‘with the compliments of Major General D.E.S., United States Volunteers’” (Brinton 1896). As with other contributed specimens exhibiting complex gunshot or shrapnel fractures, museum staff stabilized the small bone shards of the tibia and fibula with bits of wire and mounted the specimen for study.

Surgeon General’s Office specimen photograph for Maj. Gen. Sickles’ right tibia and fibula comminuted by cannonball. National Museum of Health and Medicine, Otis Historical Archives, SP 43.

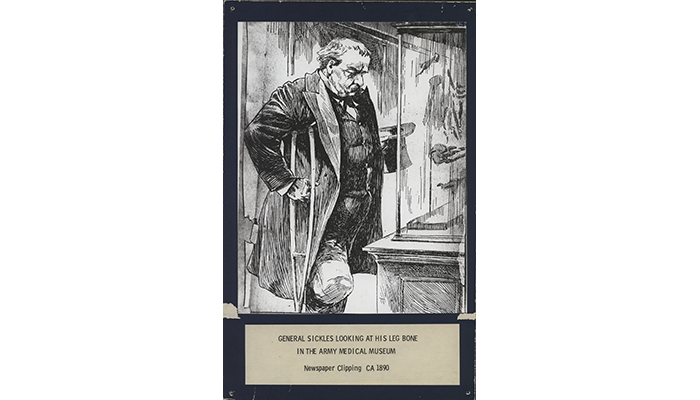

Sickles’ relationship with his amputated limb did not end with his operation, nor with his donation of the leg to the museum. For years after the war, Sickles visited the museum display of his shattered bones, often with invited guests. The limb took on an importance of its own, as observed by the author Mark Twain, who wrote after a visit to the general's home, “I noticed then, what I had noticed once before, four or five months ago, that the general valued his lost leg away above the one that is left. I am perfectly sure that if he had to part with either of them he would part with the one that he has got” (Twain 1924: 339). Today, the fractured tibia and fibula of Maj. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles are still on exhibit and continue Sickles’ legacy of educating future generations, just as he desired.

Resources

Accession File, AFIP 379085, OHA 31, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Brinton, John H., Personal Memoirs of John H. Brinton, Major And Surgeon U.S.V., 1861-1865. New York: Neale Pub. Co., 1914.

Brinton, John H., Valedictory Address to the Graduating Class of the Army Medical School, Washington, D.C., March 18, 1896.

Daily National Republican, Washington, D.C., July 6, 1863.

Hessler, James A., Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg. Savas Beatie, 2009.

Twain, Mark, Mark Twain's Autobiography, Vol I. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers, 1924.

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.