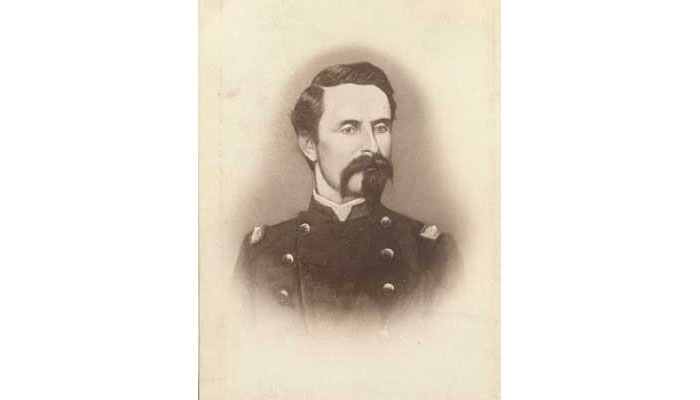

On the afternoon of July 1, 1863, U.S. Army Lt. Col. John Benton Callis of the 7th Wisconsin Infantry was in serious trouble. It was the first day of heavy fighting at the Battle of Gettysburg, and his men were in retreat. The general of his brigade, most of the field officers, and his horse had been wounded or killed earlier that day, and the Confederate forces were closing in on both flanks. As he tried to reach safety, Callis was struck in the chest by a conoidal bullet that fractured his right 10th rib, passed through his liver, and lodged in the lower lobe of his right lung.

His regiment was captured and Callis was left for dead. Helpless, he lay injured while Confederate soldiers searched through his pockets and stole his belongings. The items were soon returned by a Confederate colonel, who, upon discovering that Callis was born in North Carolina, assigned two Confederate privates to watch over Callis and make certain no further harm came to him. Callis later wrote, "I was left on the field, supposed by my regiment to be dead, for 40 hours during which time I was in the hands of the enemy." I was suffering the most intense pain in the region of the liver and right lung. I raised blood from my lungs" (Callis, 1863). He also reported severe pain in his right shoulder and partial paralysis in his right arm and leg.

On July 3, still on the battlefield and afraid he would be trampled during the Confederate retreat, Callis convinced his guards to carry him to a private residence where they hid until the U.S. Army regained control of the area. Callis was moved to another residence where he remained under the care of Union physicians for two months with the bullet still lodged in his body. He writes, "My surgeons said I could not live. They had no hopes of my recovery for the first six weeks" (Callis, 1863).

Treatment of the injury included counter-irritation over the liver and lung (applying an irritant to the skin to distract from deeper pain), morphine, tonics, stimulants, and hearty food. The external wound eventually closed, and on Sept. 1, Callis began the journey home to Wisconsin. Along the way, an abscess in his liver ruptured and drained into his lungs, causing Callis to cough up bile. The discharge continued when he reached Wisconsin and coughed up a quart of bitter yellow-green fluid mixed with blood.

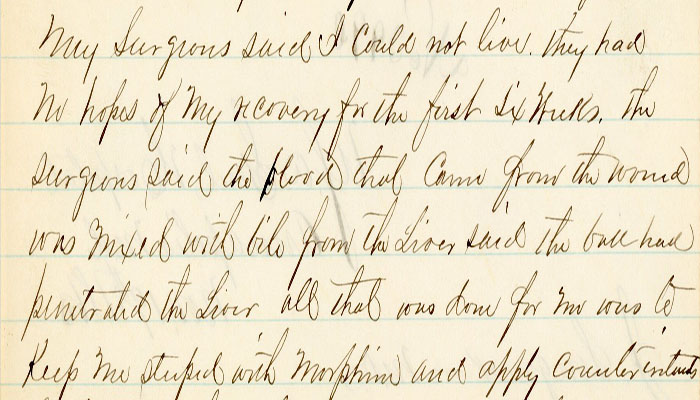

Excerpt from the medical report of John B. Callis, November 18, 1863. OHA 31, Otis Historical Archives. AMM PS/SS 3990.

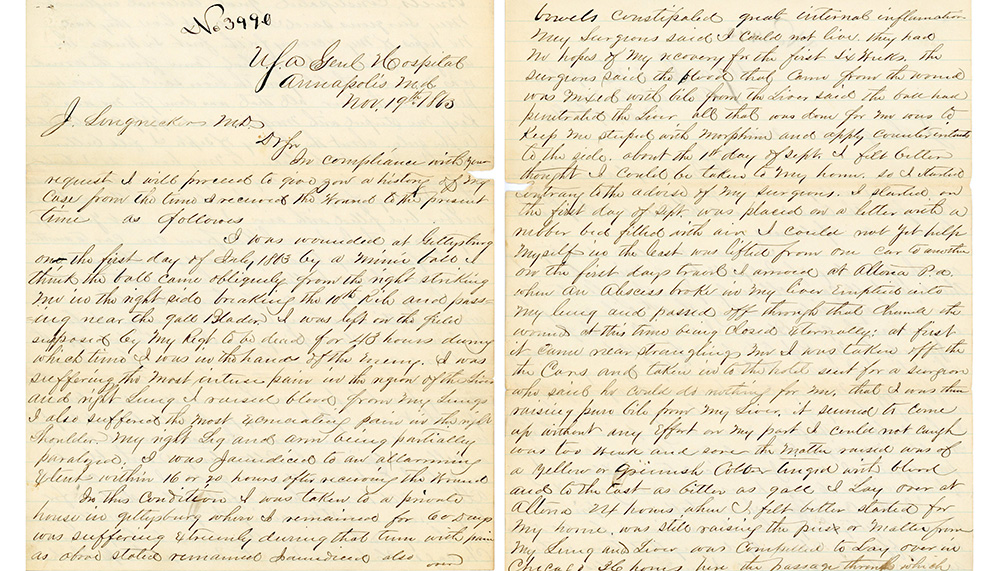

In November 1863, Callis was transferred to the U.S. Army General Hospital in Annapolis, Maryland. He wrote:

Medical report from John B. Callis, November 18, 1863. OHA 31, Otis Historical Archives. AMM PS/SS 3990, pages 1 and 2.

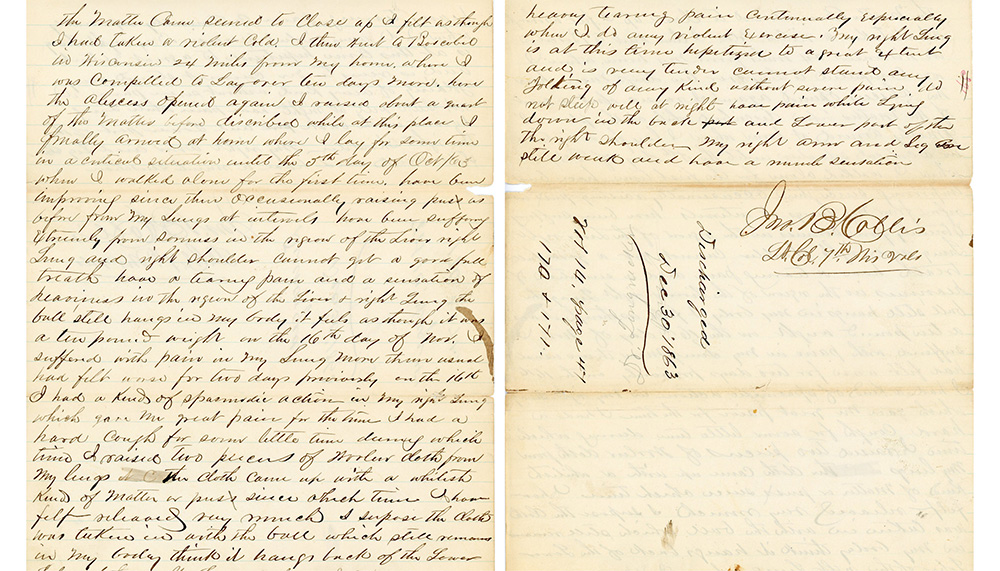

Medical report from John B. Callis, November 18, 1863. OHA 31, Otis Historical Archives. AMM PS/SS 3990, pages 3 and 4.

Callis was medically discharged from the U.S. Army on Dec. 28, 1863, defying the odds to survive both the initial gunshot wound to the chest and the subsequent infection. He later joined the Veteran Reserve Corps, was appointed as military superintendent of the War Department in Washington, D.C. and served as a commissioned officer with the U.S. Army, stationed in Huntsville, Alabama. After his military service, he briefly served in Congress representing Alabama's 5th District. Callis died in Wisconsin on Sept. 24, 1898, at the age of 70. The bullet was never removed from his lung and caused him pain for the rest of his life.

Resources

Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774 – Present.

Brown, M. A. W.; Brown, Hiram O., eds. (1890). Soldiers and Citizens' Album of Biographical Record of Wisconsin. Grand Army Publishing Company: 391-394.

Callis, John B. (1863). Medical Report, AMM PS/SS 3990. OHA 31, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Clark, Walter, ed. (1901). Histories of the several regiments and battalions from North Carolina, in the great war 1861-'65. Vol. 5: 611-616.

United States. Surgeon-General's Office. (1870-1888). The medical and surgical history of the war of the rebellion (1861-65), Surgical Vol. 1: 585.

_Banner Image.jpg)

An official website of the United States government

An official website of the United States government

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .mil website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.